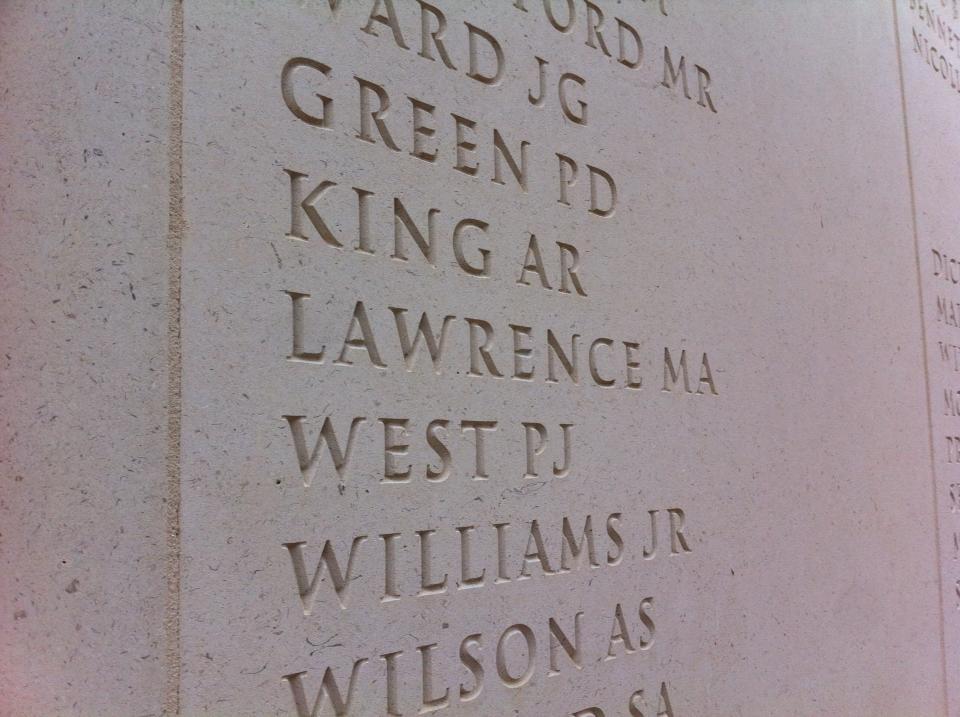

Elaine was born and raised in Margate in Kent. She was engaged to be married to Lieutenant Marc Lawrence, who served in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm and died in a helicopter collision in the North Arabian Gulf in 2003. Elaine explains her position as a fiancé, rather than a wife, whereby she had to prove she had a ‘significant and long-term relationship’ with Marc before the Royal Navy would grant her his service pension, even though she was listed by Marc as his next of kin. Elaine was not deemed eligible to receive a War Widows’ Pension as they were not married. Elaine talks about her childhood, her education, her long distance courtship with Marc, how she coped with his death, and her life as a successful business woman running a consultancy company with her husband. This interview was conducted by Melanie Bassett on 6 December 2018.

Click here to download the transcript of this interview as a pdf file.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

Okay. I’m Melanie Bassett. I’m here interviewing Elaine Gosden for the War Widows’ Stories project. It’s Thursday, 6 December 2018. Hi Elaine, thank you for being interviewed by us. Could you state your name and your age, please – the year of your birth?

Oh. Yes. Elaine Gosden, and I’m 38. Am I 38? Yes. I was born in 1980. It’s my birthday soon.

What is your role at the moment? What’s your current situation?

Jobwise? I am the Director of a company that I own with my husband.

And what’s the nature of that?

It’s, well, this is a complicated question because we have two sides to our business. So there’s my side and there’s my husband’s side, and we both operate under the same business name, which is Blue Gnu Consulting. We’re both consultants but I do learning and development training workshops for, typically, corporate organisations and my husband deals with medical data and helps to get pharmaceutical products to market. So he helps with gathering data around new drugs, their efficacy and cost-effectiveness and hopefully influencing government bodies to prescribe them. I can’t do that, [laughs] so he does that and I do my bit.

So could you tell me a bit about your childhood and early life, where you were born and brought up?

Yes. I was born in Margate, in Kent. And I lived with my parents happily for the whole of my childhood, pretty much, but when I was 10, nearly 10, a little surprise arrival of a baby brother happened. And then when I was 12, another surprise arrival of a little baby sister occurred. So I am one of four. And I have an older brother, and myself, we’re two years apart, so I’m second. Then my younger siblings arrived ten years later, randomly. So yeah, family life was interesting. We grew up on the edge of a council estate, we didn’t have much cash. It was a case of; Dad brought the wages home on a Friday, we paid the bills and did the shopping on a Saturday – it was a very hand-to-mouth existence. And then certainly, when the little ones came along, things were a bit tighter. So it was all a bit um… not stressful, I don’t think my parents ever felt stressed about their life, I think they were very happy, but it was a very simple existence. There were no holidays, no flash cars, no big house. It was just, we did what we could with what we had, and it was nice that way.

Did you find you were doing lots of babysitting when you were…?

Not so much babysitting as my parents never went out, much, but I did have a huge role in the upbringing of my brother and sister, to the point when my sister was born, my mum had quite a lot of medical complications so she had to stay in hospital for quite some time. And she had a hysterectomy, which, in those days, nearly 30 years ago, hysterectomies were a really big deal. So she had to stay in hospital for six weeks with the baby, and we had a 2-year-old, so she took me out of school for the whole time. I remember it, I was in Year 8, and she said to the school, “I’m really sorry but my daughter needs to stay at home to look after her brother,” because my dad had to go to work or we’d have no cash.

My dad worked in a factory. So it was a case of, if Dad didn’t go to work, we’d have no money. So my dad couldn’t stay at home to look after my brother, so I was the chosen childcare provider. I’m not sure how the law or how society would look on that these days but my mum just wrote a note to school, saying, “I’m really sorry, she’s not coming for a few weeks.” So that was that. And I remember clearly walking into town, we didn’t live too far away from the town centre, and um, I remember quite clearly walking into town with my little brother in a pushchair, and some of the older ladies frowning and tutting, saying, “The youth of today!” as if the baby was mine! And um, he obviously wasn’t mine, and I made a point of telling them that. But it’s funny how people judge you when you’re a young teenage girl and you’ve got a baby in a pushchair. So yeah, it was quite interesting. But very happy. We were always having fun, sharing bedrooms, with bunk beds in every room and it was a very small house for six of us to live in but we did it. It was good.

Did your brother take on a role?

Not really. [Laughs]. Oh no, bless him, he wasn’t particularly child-minded. Also because he was a couple of years ahead of me, he was at a bit more of a crucial point in his schooling than I was. So, he was just about to do GCSEs so you know, it was more important for him to go to school and get his grades than me, I guess. Plus, I didn’t really mind doing that kind of thing. So, you know, it was like a “real-life dolly” situation, so. And my younger brother, Adam, and I, are quite close and I think that’s probably because I helped out with him when he was a dinky one. I’ve got lots of lovely memories of family Christmases and me going out with my friends as an 18-year-old and getting drunk in the pubs and rolling in on Christmas Eve at 2am, and having strongly briefed the little brother the night before, and the sister, to say, you know: “As soon as you know that Santa’s been…” because, you know, we had to – we lived the ‘Santa years’ right up until I left home, briefing the children, you know, that they must wake me up. So oftentimes, I’d get in from a nightclub at 2am then they’d wake me up at 4, to open Santa’s presents. [Laughs]. And then, then we’d be up from that point on. So there’s lots of lovely family memories. Bless them. But we’re all scattered around now, everyone’s gone in different directions. My sister still lives in Kent but even my parents have moved away, and both my brothers live elsewhere. So.

Do you have any military connections in your family?

Hmmm. I did do my family tree for my father actually. When my dad turned 60, I researched our family tree on my dad’s side, partly because someone else had already done it on my mum’s side but no one, to my knowledge, had ever looked into my dad’s family history. And dad – my dad knew that his family had army connections but it was hundreds of years ago. I discovered a few chaps who had been to India prior to the First World War and around the turn of the 20th century, like 18—whatever, going off to some really exotic campaign locations, and finding their military records and everything like that was really exciting, I really enjoyed doing that. Um, but not in recent years, directly. But I have many cousins, both my parents are from large families, and some of my younger cousins are, I believe, enlisted. One of my younger cousins is a marine, another one is in the army. But not directly, not really.

Can you tell me about your education? Did you go to college or university?

So I went to grammar school in Kent. They still had a grammar school system, so all four of us actually passed our 11-plus and went to grammar school. We all chose the same school to go to even though we had a choice. It was a single sex school or a mixed school, we all went to the mixed school. But I was very clear… I’m not really a – not really a rule-following type of person, I’m not that conventional, and a lot of my friends wanted to stay on after GCSEs to the sixth form and do their A Levels then go on to university, as that’s what we were all being groomed for, I guess. In a grammar school system, it’s expected, I guess, ish, that you might head off to university. And I didn’t want to do that so I had my eye on more of a vocational route, so there was a large company a few miles away from where I grew up in East Kent, and they were the biggest and best employer in the area and everybody knew that they paid well and it was a really great company, and thousands of people worked there and you were really lucky to get a job there. It was like, you know? It was real, a real thing.

And so I targeted them because I knew they were doing what nowadays I guess you’d call a modern apprenticeship scheme. So, at the time, it was just called a YTS, a Youth Training Scheme. And at that time, I thought I wanted to be a secretary, so I enrolled on this – got interviewed and I had to go to these glamorous buildings and go through lots of processes to get the job, but basically I got a trainee secretary’s job there, which involved four days a week working in the office and one day a week going to college. I did that for two years, while my friends were doing their A Levels. But I realised it was actually quite easy being a secretary. Apologies to any secretarial people out there, but I found it quite straight forward so I actually went to evening college as well and did a couple of A Levels in my evenings because I felt like I could, and that suited me better. I did distance learning so I had a tutor and I had some … these days you’d probably do it on the internet but I just had ringbinders upon ringbinders, upon ringbinders of ‘stuff’ to study, and yes, I managed to get two A Levels and my secretarial qualifications within that two-period. And I was super-lucky-slash-worked really hard and my boss at that company, at the end of the two years, offered me a job. So I got straight into work at 18 when all my friends were heading off to uni, I was heading into work, which suited me down to the ground. That’s what I wanted, that’s why I did it that way. So I didn’t do a conventional route, I didn’t do further education and university in the same way as a lot of my friends and peers have done.

Brilliant. So if we can move on to talking about how you met your fiancé – late fiancé – can you remember your first date?

I don’t think we had a first date as such. I think, I remember first meeting him. Ummmm … and it’s a funny, slightly inappropriate story, but it’s quite funny so I’ll tell it anyway. But um … my best friend, a girl called Laura, and I have been best friends since we were in senior school together. And she had an older brother – she still does – [laughs] called Mike, and Mike lives in the States. He had, I guess back at that time, he must have fairly recently married his American wife so they were maybe two or so years into their marriage, and Mike’s a schoolteacher so he comes home to England typically for a holiday during the school summer holidays, and in California, they start their holidays in like June/July. Anyway, Mike came home for Christmas and Laura and I had been really close,[1] we’d both sort of split up with boyfriends and we were both there for each other, you know? And she’d said, “Oh, my brother’s coming home.” I knew her brother anyway; I’d spent many a time in her house with her brother there and whatever. But she said, “Oh, Mike’s coming home and we’re going to have a big night out, do you want to come?” Because it was his birthday, I was like, “Yeah, I’ll come.” So we got all geared up to go to a nightclub. We went to the only nightclub in Margate – it’s a very small town. [Laughs].

And I just, then just this very handsome man was there. And I didn’t really know who he was or who he was with but as the evening progressed, I kind of realised he was one of Mike’s friends, and through the drunken haze of memory, I remember spending a lot of time with him at the bar and chatting. And that evening I was supposed to be staying at Laura’s house but I didn’t go to Laura’s house, I sort of went home … he was staying with a friend but we were just chatting so much that I just went back to his friend’s house with him and we stayed up all night just chat-chat-chat-chat-chat-chatting. And then the next morning, he took me back to Laura’s house because I had to, of course, go and get my stuff. [Laughs]. And he took me back and Laura was like, “I can’t believe. I can’t believe you’ve spent the night with Marc.” I was like, “I haven’t spent the night with him like that. Like, we’ve literally been chatting the whole time.” Then about two hours later, he came back to bring me some earrings and bits and bobs of, you know, jewellery I’d taken off, and he brought that stuff back to me and it was a bit kind of … . We didn’t – it was a bit kind of “Oh, are we going to exchange numbers? What’s going to happen?” So we did exchange phone numbers but I think because I knew he lived and worked in Cornwall, and at the time I worked and lived in East Kent. It was that – it’s a long way from the bottom of Cornwall to the top of Kent, and, and he was from that area – his parents were from East Kent as well, but it was kind of obvious there was no mileage in being boyfriend and girlfriend at that stage, so he went his way and I went mine. And then we didn’t really get in touch much again until … I can tell you exactly when it was, because 9/11 happened, so this was in 2011. So 9/11 happened, and obviously that was a really memorable day for most people. I certainly remember where we were, you know, when the planes hit the towers, and I knew from sitting up and chatting to Marc all night back in the summer that he worked in military aviation and that he lived on an airport, basically. And I’d heard on the news that all planes worldwide were being temporarily grounded because obviously, at least three aircrafts were affected in the States. And so I just thought that was really significant for someone who lived on an airport so I just texted him and said, “Are you okay with all this stuff that’s going on?” You know? “Does it affect you? And, what’s going on?” Which struck up some conversation and contact, because we, we had no real reason to be in contact prior to that. And then we stayed in touch and then that year, in October, I relocated from Kent to Surrey so I moved about 100 miles west, which just meant that the thought of a relationship with someone who lived in Cornwall was a bit more ‘workable’ because it took about an hour and a half off the journey to potentially get down to see him. So that time, October to December, we started seeing each other a bit. And he would come – I lived in a big house near where I worked with lots of other colleagues – one of whom [laughs] is my husband now – so we all lived together and Marc used to come up at weekends and hang out with me. Then we realised we did want to be boyfriend and girlfriend, and then we were. But we only really saw each other at weekends because he lived “on board” as they would call it in the Navy. So yeah.

He was at Culdrose?

Yeah, yeah Culdrose. Yeah, which is a military air station down at the south of Truro in Cornwall. It’s, it’s a long way. Just when you think you’re there, or nearly there, you realise you’re not nearly there – the country just keeps on going in a westerly direction for many hours. So the drives down there, I used to go down to him or sometimes we’d meet halfway and like we’d, you know, rent a caravan in Dorset or somewhere so that neither of us had to do like a five-hour drive – we’d both do 2 and a half hours and try and find places where it was convenient to meet. So yeah, a long time ago now.

And telephone conversations, were you …?

Oh, every day. Every day. Yeah. All the t- like it was like, you know, we were properly boyfriend and girlfriend and we were on the phone every evening, emailing throughout the day, you know, as and when he could. In our quite short relationship, he only had one, well, two significant deployments – one of which he didn’t come home from. But the first significant deployment was eight weeks, when he went to the Mediterranean, and that was really hard because when someone’s living on a ship, it’s very difficult to get in touch with them because they don’t switch the communication on all the time and obviously they’re doing military exercises so they don’t want to be contacted or found from time to time, so that was a real test for us, eight weeks apart with literally hardly any contact and the occasional “bluey”. Have you heard of blueys? They’re like … I don’t know if they still do them, I think they probably do them by email now. They were certainly starting to do them by email in 2003, but the occasional little blue note would arrive through the door and … But it was really tough for both of us, I think. He found it hard being away and I found it hard him being away.

Yes, they do “e-blueys” now.

Yeah, I think they’d just started to do that when Marc was on the ship, when he was on the deployment that he didn’t come back from. It was a new experiment thing. It was like, oh, I found this e- e-thing. But it didn’t really make sense because we could email anyway so it was all … but this was in the days when email wasn’t a thing, and you certainly couldn’t get emails on your phone or whatever, it was all very … you had to dial up to a slow telephone point in the corner and wait for some kind of connection. [Laughs]. It was a long time ago.

So can you tell me about when he proposed?

Yes, I can tell you exactly about that. As young couples do, I think we’d been talking a little bit about fu- the future and whether we’d get married and all that kind of stuff but I have to say, he totally surprised me with the proposal. So in the Navy, it’s a bit like being at university, I suppose, or being at school in some ways in that you get quite a lot of holidays. Not – quite a lot of fixed holidays and time when you’re just expected to go away for months on end. But when you’re living and working in the UK, you kind of get Easter off, a bit of the summer off, some Christmas holiday, and you know, they don’t ask people to go in over those times, so he had an extended leave period in December, partly because he knew there was … well, the Navy knew there was a big deployment coming up and he’d been chosen for the deployment. So he had most of December off up until early January where they to start to get ready to deploy.

And one evening, at the beginning of December, or maybe it was the very end of November, he’d had, you know, a significant chunk of time off, and he’d come up to the house. So where we lived at the top of Headley Hill, near Reigate, he’d – in my, in the big, shared house that we had, there were loads of big bedrooms, it was like a big mansion house. And upstairs in the part of the house that I lived in, there were two large bathrooms – one en suite that was attached to my friend’s bedroom and one main bathroom that was right next to my room and between a couple of other bedrooms. And it was a large room, so probably a 4 metre-squared room and in the middle of it was this huge bathtub, and we’d loved that bath.

Like, the one thing about Marc that was significantly notable was that he was a real water baby. Throughout his whole life, he was in the water a lot. So he loved sailing, swimming, diving, wind-surfing, you know anything, actual surfing – anything to do with the water, Marc was a real fan of. So this one evening, he was like, “Why don’t we have a bath?” which was not an unusual occurrence at all. I said, “Okay.” The bath was big enough, we could both get in, yada-yada-yada. So we were in the bath. We’re in the bath and there was candles, bubbles; it was all very lovely – a winter’s evening bath. And he just leant out of the bath and got this little box and just opened it in front of me. I was honestly … if I’d been wearing socks, they’d have been knocked off. I couldn’t, couldn’t quite believe that he’d asked me. So yeah, he did, and I said yes. Then we got out the bath and I said, “Have you asked my dad?” [Laughs]. I think he had. That’s a difficult one, I can’t remember whether he had or not. But yes, I still wear his ring. I, I’ve never – I promised him that day … because he almost couldn’t believe that I’d said yes. He was a very attractive man, but for a very attractive man, he had sort of middle levels of confidence, like he certainly wasn’t one of these attractive guys that would strut around and you know … He had a few confidence issues. And he almost couldn’t believe I’d said yes, that I wanted to spend the rest of my life with him. And I sort of said – I promised him that evening, and I remember it really clearly, that I was never going to take this ring off. And he was like, “Not ever?” I was like, “No, never. I’m never going to take it off.” So I don’t. I keep it on. And my – I’m very lucky that my husband is cool with that. He doesn’t … He knows all about that situation so it’s fine. Other than when I’m playing netball, I don’t take, take it off. I’m very lucky.

Just to clarify, it’s on your right hand?

Yeah, it’s on my right hand. I’ve all my current rings [laughs] on the proper fingers. Yes, it’s on my right hand, and I did that … I wore it on my left hand for about a year after he died and then I switched it over, and it’s been there ever since.

So did you experience any base life or were you living completely off-base?

A little, in that I would go down at weekends. And I had security clearances and I could come and go from the base as I pleased, with effect, but not a lot because I had a fulltime job in Surrey, so I needed to be here for five days in a week. But I would go down at weekends and when we had time off or whatever. But I didn’t – I wasn’t very comfortable with it because there were people on the gates with guns, and I always thought that was a bit much. I understand why they’re there but you know, when you’re not in the military, it’s a bit intimidating to have to drive past serious-looking chaps with guns on – strapped to them. So it wasn’t my favourite place to be because I found it quite intimidating. But I got used to it. And I probably spent quite a bit of time living on the base after he died because the navy were very kind in letting me do that. They let me stay in his room for a bit after he died, which was really sweet of them. And it was really helpful for me because it provided me with a bit of comfort, being surrounded by his stuff and all the rest of it. It wasn’t, it wasn’t for a particularly long period of time but nonetheless, they didn’t kick up a fuss and they didn’t mind, and I had all the relevant passes to come and go, so it was, it was fine.

Did you go to any military events or dinners or were you only …?

Yes, there were lots of mess dinners, because you know, officers, they like to have mess dinners and they like to celebrate everything so there were lots of summer balls and Christmas balls. And that would be the draw to go to Cornwall, usually, was for a significant something like that. We wouldn’t necessarily spend the weekend down there just for the weekend’s sake; it would usually be, there’d be some kind of event. And you know, there was pomp and ceremony for everything so there was always a service or something going on, which was nice. Lots of, you know, “Trafalgar day dinners” and this, that and the other day dinners, and Remembrance Day dinners. There was always a dinner for something. And I quite liked that. I quite liked getting dressed up and going to those things and letting your hair down a little bit, and I think it was important for the guys to do that, because a lot was asked of the men – and women – in the Navy. They have to give a lot so it’s quite nice that they get to let their hair down and celebrate from time to time. Quite a lot of times.

Did you feel a part of the military family? Did you have other friends that you made, of women whose partners were in service?

Yeah, yes. So in the squadron that Marc was in, there are typically two students that join the squadron every year as trainees – this is how it used to be anyway – and they go through their training together and they pop out the other end hopefully, as like – they get their wings and everything, you know, and then are part of the squadron – the main squadron. Marc had a very close friend called James who he did all of his training with, and I think there was at least one or two others. But with helicopters, it’s quite tough to stay in – there’s lots of points where if you don’t make the grade, you get asked to leave. So, it’s not just the case of if you pass the initial test, you’re in. It’s a case of once you’ve passed the initial test there’s lots and lots of other tests and competencies, and skills and things that they have to develop and grow with, and, and a lot of people fell by the wayside because they didn’t meet the criteria or they, they just simply weren’t of the right standard.

But James and Marc did all of their training together and stayed together as, as, as partners throughout their training and we would hang out with James and his fiancée, Sarah. And they got married – they got engaged about 2 or 3 weeks after we did, so it was all very parallel and we would, you know, see them a lot and hang out with them a lot. And I, I, you know, I knew a lot of the guys that were a similar age to Marc. I have to say, I didn’t know many of the older members of the Squadron because there was no need for me to, but the people around the same age as, as Marc, I knew. There was a one chap, a really lovely American guy called Tom who joined the Squadron as an attachment from the US Navy, and he was lovely as he really enjoyed being – having a British life. He got a BMW and he just thought that was marvellous to have a German car. He was really full of, full of zest for life and what, not but sadly he was killed in the same incident as Marc, and James was too, so they all died together, which is really sad. But yes, I knew a lot of – particularly Sarah. She and I to this day are still in touch and there are other girls I knew at the time that I haven’t stayed in touch with as much as Sarah, I guess because she and I have the most in common. But the other – the guys in the year below Marc and James, one of them is still a good chum, and their partners I that knew. So we had a little friendship group, a little support network of people that got it, and people that understood. And if I’d lived in Cornwall, which was the plan, they would have been my support network and my go-to people, but we didn’t quite get to that stage. Because I was going to move down in the summer when Marc returned from sea, and obviously he didn’t. He didn’t come back so we didn’t really get to do that bit, but hey.

And was it a consideration, the danger of his job, when you met?

Hmm … Yeah, a little. But he would say, and which he did say this right up until a couple of days before he died, he would insist that he was quite safe because he wasn’t in a ‘militarised’ or no, a ‘weaponised’ … I don’t know the correct word. But his helicopter was unarmed; he was in a surveillance helicopter, so part of his job was airborne surveillance and control so they would have, the helicopter that Marc worked in had a big radar on the side of it, and they would typically be flying around above areas of conflict. So in. in Iraq, in 2003, my understanding of what they were doing is that they were up, flying at a safe altitude but using the radar to look down at ground troops and provide intelligence and direction to those troops on the ground. And if they weren’t doing that over land, they were doing it at sea and looking for, you know, ships and things out in the ocean. So his job, you know, he would consider it to be very safe because he wasn’t – because it wasn’t like an Apache helicopter that would have missiles and things on the side of it. You know, it wasn’t necessarily flying into combat zones, per se, and he would always describe his job as, “Oh, you don’t have to worry about me, what you need to worry about is …” and he would list his friends. One of his good friends, Simon – I’m still friends with to this day – worked in Lynx helicopters, which were usually flying off with destroyers, so a bit more active I guess in their job roles than the Sea Kings were. So he would say to me, “Oh, you don’t need to worry about me, you need to worry about Simon. Don’t worry about me.” Because he considered himself to be quite safe, hovering around looking at things. [Laughs].

Do you remember the last time you saw him?

Yeah, yes, very clearly, yeah. I had to leave him in a car park. [Sobs]. It’s funny how it makes you sad. It’s a long time ago. It was in the car park outside the accommodation block that he worked [lived] in. And we knew it was our last day together and so we’d done lots of silly things together, which were very cute and very silly. So we’d gone to the local curry house and bought onion bhajis, and had like a ‘last supper’ of onion bhajis together because we just enjoyed them. And then we’d always say, “Whenever we’re having an onion bhaji, we’ll remember this,” you know, it’s very sweet. And I had a little sports car that he’d encouraged me to buy, we’d bought it together – had a little two-seater MG, which was gorgeous. It was January, a few days – was it? A few days before my birthday because I think he deployed on the 16th or somewhere between the 13th and the 16th January. He was flying off to meet the ship.

The ship had been in Scotland and getting all filled up with supplies, then the ship was going to sail down the west of the UK, and as it was sailing down, the helicopters based at Culdrose would fly onto it. My understanding was that was happening really early on a morning, of whatever day it was, and so I left him in the car park faced with a 5-6-hour drive home. And, I can just remember … I can tell you exactly the space I was parked in, and, you know, we said goodbye, and it wasn’t like, “Oh bye, see you later then …” We knew it was a long deployment and we knew … Although we hadn’t declared war, it was all in the news at that time about Saddam Hussein and weapons of mass destruction, and ‘does he, doesn’t he?’ It was all very clear that the ships were being positioned to go there. We weren’t at war until March but they knew where they were going, they kind of, they had that. And he knew he was going to war. In fact, in the days running up to it, he – we went to the barbers in Falmouth, which was the nearest big town to Culdrose. He said, “I’m going to get my ‘war haircut,’” and he had all his hair sort of shaved off to go to go to war. So. So yes, I do remember very clearly the last time I saw him. It was very emotional. It was hard to say goodbye.

Can I ask you for what period was he over there before you got the news of the accident?

Ummm … It was all very badly handled actually by the BBC and by the Navy. They didn’t do a very good job and I don’t think they’d mind me saying that, of how they handled the communication following the accident. So, the ship had been in the northern Arabian Gulf for at least a week before the accident had happened. War was declared, I think. I need to check my facts but I think it was declared on the 18th/19th March, something like that, and then Marc died on the very early morning of the 22nd. And we’d spoken the night before. So things were in train for our future. So the big, shared house I mentioned that I lived in, I was moving out of that house because everyone … We’d all moved there as part of the relocation from Kent to Surrey, so it was always going to be a temporary place to live. We lived there for a year and a half, and then everyone started to buy their own houses or drift off into relationships or wherever, whatever; we were all going. People started to head off. So as a group of friends, we had identified this particular weekend in March that we were going to move out of our house, and … And I had arranged to live with a friend of mine, a female friend who’d recently been divorced, who had spare room. She needed the company, I needed the company because my partner was off for months and I needed to save some cash because the plan was, as soon as Marc returned we would buy a house. In fact, I was already on the list of estate agents receiving property details and kind of beginning to scope out the market for where we wanted to be.

So, it’s a complicated story but essentially, Marc died very early on a Saturday morning; on the Friday night I had started to move my stuff to my friend’s house because the end of the tenancy was the Saturday, or Sunday maybe. Um and so I’d started to move my stuff. I had said to my friend who I was moving in with, “Oh,” you know, “I’ll come and stay with you from the Friday night.” So I was in her house on the Friday night. And my phone rang, and it wasn’t a fancy phone like we have these days; it was a big old Nokia brick. But my phone rang and – a number I didn’t know, and it was Marc. He’d phoned. It was about 9:30pm on the Friday night. And he’d, he was just so excited that the ship’s communications had been switched on, because they were effectively in the dark zone i.e. very little communication, not wanting the ship to be identified by, you know, ‘the baddies’ and all the rest of it. They didn’t have the communication from the ship switched on a lot.

So he was just about to go out on a sortie, and he had … the communication had got switched on just as he was getting ready to go so he managed to get in one of the phone call queues and make a call off. So he’d phoned me, and we had a lovely chat. And he was telling me all about how much flying he’d been doing and how busy it was, and how “This is why I joined the navy” and he was just totally buzzing from the energy of a ship, being there doing what they’ve trained for all these years. And he was absolutely loving it, and he was excited to hear from me about the fact that I’d started moving, and the fact I was at Vicky’s house and the fact that, you know, essentially it was another step closer to us doing what we wanted to do, which was to buy a house together and get married and all that stuff. And we’d booked the wedding. The wedding was … we’d sorted that out during the Christmas holiday after he proposed. So the wedding was happening, we had the date for that, so it was just about getting everything else in position and getting him home again in order to make that happen. So … Um …

I’ve forgotten your question and why I went round that big roundabout, but it was all to do with the communication or how I found out, that’s what it was. So I’m staying at a new house, I’d spoken to Marc about 9:30. We’ve had maybe a – they’re not allowed a lot of time. I don’t know what happens now but they had these little credit card things with phone credit on. So he’d, you know, used up his phone credit and we’d said goodbye and “I love you” and all that stuff, which I really, since then I’ve held onto that as a really good thing, that I managed to speak to him and tell them I loved him, and he told me he loved me. And we were in a sweet spot, we were happy, we were doing what we wanted to do. And then he went flying and that was the last flight. So I literally spoke to him about five hours before he died, which was great. But how I actually found out about … Well, I didn’t find out about death, I found out about the accident first. So Sarah, who I’ve mentioned already, she was at university in Liverpool, and my phone rang probably at 7:30 maybe 8 o’clock in the morning. On the Saturday, which is unusual, and she said to me, “Have you seen the news?” I said, “No, I’m in bed. It’s Saturday morning, of course I haven’t seen the news.” And she said, “You need to switch it on now.”

So I had put my TV in my bedroom so I did switch on the news and sure enough, standing in front of us, is Alan Massey, who was the captain of the Ark Royal, stood there talking about an accident of two helicopters hitting each other. And you sort of listen to the news, and I had Sarah on the phone, and I was listening to what he was saying, and they were saying it was 849 Squadron. And you’re like, “Well, that’s our squadron …” And it was two Sea King helicopters. “Well, those are our helicopters …” And we know, if we don’t know them personally then we know who the people are in that squadron, and they were reporting seven people dead. And straight away, there was something fishy about that because the helicopter crews flying in threes, so why are there seven dead? And then in the next breath they were saying it was six Brits and one American. So we know the American is Tom because he’s the only, he’s the only goddamn American in the squadron.

So, they made a lot of errors because nothing had been communicated to anybody at this stage and yet the captain of the ship is standing on BBC television, live from the side of the boat, like from the ship. Talking to the BBC film crew. We knew a BBC crew were on board, partly I guess because the BBC had made that happen, because they knew we were going to war and I guess they wanted ‘live updates’ from the war zone – [ironic voice] “Like how exciting and dramatic?” But they were also filming a documentary which was aired on TV a little while later, called HMS Ark Royal about life on board, so they happened to have a TV crew there but then this horrible tragedy happens. But between the BBC and the Navy, they kind of messed it up a bit because they shouldn’t really have been reporting all of the detail that they were reporting before families found out.

And my understanding is that since the accident, because a lot of families were very cross – understandably so – is that the next of kin informing process has changed quite drastically since that conflict. And I don’t think it’s just us, but I think in many military squadrons if its, if they are based or different units … If someone’s reporting, saying, you know, “A soldier from 21 Brigade …” or whatever, you can’t – if you’re attached to that brigade or that particular troop, you kind of know that it affects you. So I heard that news from the BBC at about 8am and they were putting a thing on the thing … a number on the TV, that “if you suspect this affects you …” which you just think that’s a bit arse about face, that I should know if this affects me before I see on the television. But there was one of these numbers, of you know, “Call this number if …” So I got off the phone from Sarah and called the number and of course, as soon as I gave his service number, the person that I’m speaking to on the screen must absolutely know that my partner’s died but they’re not able to tell me because that’s not the process. The process is: An officer will visit you with a priest, and then you kind of know that your partner’s dead. But because I am on the phone to them and because I happen to be moving that day, they’ve got my old details.

So, and they’re asking on the phone first of all, all about Marc and what his service number was and about what I knew about his attachment and where he was. But then they go on to ask, you know, where am I? Because obviously, they need to get to me. They know that and I don’t. So I’m like, “Oh, well, it’s complicated. I’ve kind of got two addresses today. I need to go back to my old house and move the rest of my stuff because I only moved enough pretty much to stay the night.” And so the person on the phone obviously cannot say to me, “Well you kind of need to stay where you are.” So I was in a bit of shock at this stage so I said, “Well, look, here is my new address,” in this house in Reigate where I’d moved with my friend. But they had my old address as well. And then once I’d got off the phone, it was just a case of waiting. And waiting, and waiting, and waiting, and a lot of waiting. And by this stage, I had called my parents in Kent and they’d said … even though we didn’t have any news, I think they had a sense that it was going to be a tough day anyway, so they’d came up. They’d came to my friend’s house to visit me there and bought my brother and sister who were 13, and probably 11, at that stage. And we were all sat around drinking hot cups of tea, waiting for news which just didn’t come, and just didn’t come, and just didn’t come. And so then you start to convince yourself, “Well the news can’t be coming. If they haven’t told me by now then maybe it’s okay.”

And um Sarah rang me at about … I forget the time exactly, but she rang me maybe between 10 and 11 o’clock in the morning and she just … she was just crying so I knew that James had died. [Voice waivers. Sighs] And then because I knew James had died, your brain starts to play tricks on you. You start to imagine that you are going to be affected and then you imagine that, well, it can’t be by now, if she knows and … We’d been frantically trying to get hold of other people that day and no one was answering their phone. And we now know the reason why no one answered their phone. And again, another mistake from the Navy, is they had allowed all surviving members of the Squadron, so anyone who was alive, a call off the ship at about 5am. So all the girlfriends of the guys that were alive had received a phone call saying, “We’re okay,” which is why we got radio silence. So I rang a couple of girlfriends whose numbers I had and left voicemail after voicemail – “have you heard anything? Is your partner okay? I still haven’t heard anything.” Der-ler-ler … And how heartbreaking for them to see missed calls and to hear our voices on the other end of the phone and they already knew what we didn’t know. [Takes big breath out] Which is just a huge amount of error on the Navy’s part, and for which they never really have directly apologised for that but hey, there’s a lot of water under the bridge now.

But. So I didn’t find out for a long time and it got to the stage where I was so bored of waiting and so kind of, well, “If they’re not here now, they’re probably not coming.” So it probably got to about 1:30, 2 o’clock that day, and I said to my parents, I was like: “I can’t just sit here any longer. I’ve got to go back to the old house and pack up the rest of my stuff.” So I went back, my parents came with me and we drove over there and we started packing away stuff that needed packing away and der-der-ler-der. Then my phone rang and it was my friend, Vicky, who I’d just moved in with, and she said to me … Bless her, she was trying to not tell me, but almost just by phoning me, she’d told me. But she said, “Oh, can I speak to your mum? I think she’s left something here,” and I knew full well my mum had not left anything at Vicky’s house because she only had my dad, her handbag, and my brother and sister with her. So I knew in that moment that he’d died and that the Navy were at her house and obviously I wasn’t there, I’d gone to the other house. So that – I’ve sort of – my, my memory has sort of blanked that little passage of time out because it wasn’t very nice and I – there was lots of … I, I’d just collapsed, dropped the phone [makes ‘bleugh’ noise], got a bit upset as you would. And then probably about 20 minutes later by the time I had had my initial shock, horror, the people who had gone to Vicky’s house rocked up at house. And then by that time, I was just so pissed off with them. I was just so cross with them for fucking it up – excuse my language. But they, they fucked it up left, right and centre, and we’d waited a long time for them to fuck it up so royally. So they, they arrived, and by that point, I was so cross with them, so cross with them. Then to make matters worse, they have to … part of the process used to be – whether it’s the same now I don’t know – but they have to hand you a piece of paper with the facts on it so, you know, the person’s name, their service number, the fact that they’re dead. And I’ve still got the piece of paper, it’s a bit dog-eared now, but I’ve still got it.

And what really peed me off about that piece of paper – and they got the full force of my anger at this point because I’d had the initial upset and now I was just cross with them – is that they didn’t spell his name right. And, I just sort of think; it’s the basics, like it’s just a name I know, but how you spell your name is how you spell your name. And he’d been in the military for, you know, 4 years/5 years maybe. So how does your employer misspell your name? But they had, they’d spelled it – Marc spelled his name with a ‘C’ and they’d spelled it with a ‘K’. And that was one of his pet hates. So I just shouted, a lot, at the man. And I just remember this priest guy having this vice-like grip, holding me on the sofa because I was so, so cross with them. And obviously, they’re trained to deal with that said, so they were probably expecting me to be cross with them. But, it could have happened in a far better, far more coordinated, and far less exposing way for me, because lots of people said afterwards that as soon as they saw it on the news, even though they weren’t reporting names, people knew. Because even my friends knew what squadron he was on and what ship he was on, and the fact that he was out there. And I don’t know how many crews they had out there, they probably about five or six helicopter crews, and two lots of crew members had died so it’s only a process of elimination to work it out.

And, if I’d known that on that day what I know now, I’d probably have been even more mad about it, especially that some of them … well, all the guys got to phone off and phone their family members to say they were okay. If I’d known that on the day, I’d have been furious, absolutely furious. Um … So yeah, it was handled badly from start to finish, and then to top it all off, [ironic laugh] to top it all off … Bless Marc, he was a water baby through and through, and the poor chap was missing in the water for a long time. So, some of the bodies were pulled out pretty quickly, because they’d collided over water, so there was a huge explosion and wreckage going into the sea and bodies going into the sea. And some of the guys were pulled out straight away, James was one of the first to be found and pulled, and obviously dead. It was not an accident that anyone could have survived. And some of the guys, it took a few days them to find, some it took a couple of weeks. Marc didn’t want to get found straight away; he’d been flung quite some distance – where they eventually found him it was quite a long way from the scene of the accident. So, he was missing for 10 weeks. Which is a loooong time, and by that time the Ark Royal had come home; it was already moored up in Portsmouth. I’d gone down with my friend, Simon, who was Marc’s best friend who was on HMS Liverpool in his, in his Lynx. I wanted to go and see the ship. I wanted to go and see Marc’s cabin and I really wanted to meet Alan Massey because I was very cross with him. And so I did. I had tea with him in his captain’s suite. It was all very polite and civil for some of it, and then I just explained to him just how cross I was with him because he was having tea with me in Portsmouth, and he’d left a crew member as far as I was concerned. He’d – Marc was the only one that didn’t get brought home, and I was absolutely furious about that.

Um and then, random coincidence or I don’t know what, I don’t know what these things are, but literally that day … I’d had had tea with Alan Massey, I’d been cross with him. I’d explained to him how I thought what he had done was unacceptable. And of course, it wasn’t his fault, and I know now that it was just the grief talking, but nonetheless I was pretty cross with the man – rightly so, I think. And that afternoon, once I was off the ship, someone came, I can’t remember if it was Simon who said it me or some random other Navy person that was hosting me that day said, “Oh, there’s someone in an office building here somewhere that wants to meet with you.” By that stage, I’d met with so many military people, I was like, “Oh, for God’s sake, really? Another person that wants to say how sorry they are or wants to …” You know, you get to a point with that where you’re just like, “Enough already, I don’t care really about any of these people.” Because grief is quite a selfish thing. And I was taken into someone’s office, crikey knows who the person was, I don’t remember, and they sat me down and they told me that they’d found him that day, just after I’d had my little rant at Alan Massey.

And then I got cross with them for finding him! [Laughs] So I was cross with them for not bringing home, and then the day they found him, I was absolutely furious with them for finding him. I was like, “Well, you can put him back them because he’s been there for 10 weeks and I’m pretty sure that’s where his resting place is, so can you just leave him there?” And I was like, “What do you think you’re doing, picking him up from the seabed now?” Like, “That is just ridiculous, just leave him where he is …” But it wasn’t my choice, they had to recover him once they’d found him, and then it took a few weeks to get – get him home. And he got repatriated in the same fashion as all the other chaps that already, months, weeks ahead, weeks previous, had been bought home. So I’d been to quite a lot of funerals by this stage but hadn’t had a funeral of our own. We did have a memorial service about 2-3 weeks after he died but we, we couldn’t have a funeral without him being found. Then we did eventually have a proper funeral with a coffin and a cremation and all that jazz … Afterwards. But I was proper cross with them for finding him, which I don’t know if that’s the right thing or the wrong thing, but that what it was.

Can I ask you about the process? You weren’t married at the time, were you put down on the paperwork as the next-of-kin?

Um hum. Yes. So there were two pieces of paper that confirmed what I knew, that Marc and I were in a long-term and substantial relationship but I did have to go through a process of proving that, which was, again, a bit degrading, after his death. But whenever, I don’t know about other services, but certainly in the Navy, whenever a ship is about to enter a war zone, everyone on board is asked to go to, you know, the writer’s office and fill out a will form, effectively, a wishes form for in the event of their death, you know, what they want. And Marc had done that back in … I don’t know, I’ve got the paperwork somewhere but he had done that and he had written a will and put me down as the sole beneficiary on his will. He’d also put me on his next-of-kin list as well. So although we weren’t married, I was there on the paperwork as being like a ‘partner,’ and then one of the Warrant Officers who was …

There were lots of people that came to support, and lots of people that were very helpful and friendly, and there’s a lot of things you don’t really feel like doing after someone’s died and one of them is all the admin and signing stuff and whatnot. But there was this lovely guy called Wally. I won’t forget Wally, he was a really nice, bubbly chap who sort of managed to smile his way through everything. But he came to the house and he was incredibly helpful in explaining some of the more tricky stuff; that I had been put on a next-of-kin list and all the rest of it, and if there were any benefits to be paid out in the event of Marc’s death, then that they should come to me. But in order for that to happen and to get the signing on the dotted line, I had to go through an application process to prove that Marc and I were in a long-term substantial relationship. So, things that you never think at the time of having, or of needing to prove, but I had to provide evidence, bizarrely, that we were engaged. We, we – I had to … The things I ended up showing, which we had anyway because we were … as much as we didn’t live in the same house because he lived on board, our lives were very much intertwined. So I mentioned that I had a two-seater sports car, we owned that car together. He paid for half of it and I paid for half of it, so we had made significant purchases together, that was one of the criteria. And we had the date of our wedding booked and we had paid the deposit on our wedding venue, so that was one of the things. We had a joint savings account, which we were both ploughing money into for the purchase of the house and payment for the wedding or whatever, and we had direct debits going into and out of each other’s bank accounts, although we didn’t have a joint account other than the savings account at that time.

So it was all those kind of admin-y things that when you’re just in the process of beginning to spend the rest of your life with someone, you don’t really think those things are going to be significant or important. And I found that at the time, although Wally was lovely, the whole process was quite degrading because anyone that knew Marc knew we were together, knew we were very happy, knew we were going to get married. But you had to explain it to a room full of strangers because they need to dot the I’s and cross the T’s, which is just a due process. I get that it’s a process that you have to go through, but had he died a year and a bit later, after the 22nd June 2004 [26 June 2004],[ which was the date of our wedding, I wouldn’t have had to any of that. It’s still quite surprising how antiquated some of the processes are in the military that you have to go through, and it does make me wonder about other widows, and especially “widowed fiancés” rather than widowed married women, and about how many people there must be out there who may have ‘failed’ that process, who didn’t perhaps have enough evidence to prove their love. It makes me quite sad to think that, especially in this day and age, when marriage isn’t such a thing, it’s not … You know, you can live with someone and have their baby and you know all the rest of it, but as far as the Navy were concerned at that time, that almost wasn’t enough. So it was all a bit, a bit strange really, as if losing your partner and effectively the rest of your future, or what you thought was your future, and trying to process that, you’re having to process all this kind of crap that goes alongside it of having to prove that that was a thing. And it sort of makes you doubt yourself, which is ridiculous – that’s the last thing you want to be doing when someone you love has just died. But that’s, that is what happened, and the people that helped me were good at their jobs; they got me through it, but it wasn’t a particularly nice process to have to go through. It felt a bit, “Really …?” But that’s what happened.

What was the support like from family and friends?

Um … So … Good. My parents were very brilliant in the, in the first few days, on the day we found out which was the Saturday, and we’d started the day at my new house when I found out the news. I was at the old house I was moving out of, and eventually by the time the padre and the officer came to tell us, by the time they left which was a few hours later as everyone was in shock, and it kind of put the kibosh on moving house that day for a bit. But by the time they left, my parents had decided that the best thing for me was to go home with them. And I couldn’t really drive, I was so, like, dumbstruck. They just put me in the back of their car and took me home. I was at home for a bit and I just remember that being a really bruising feeling, of number one: Losing your partner and all the kind of hope that. Whoosh … all that hope and energy and love and excitement you had just being totally eradicated and not obviously through your own choice. A really debilitating position to be put in.

So my parents did the right thing in taking me home but by taking me home, it sort of exacerbated some of those feelings because it wasn’t my house. You know, I’m a very independent person, I always have been, and I didn’t have my car, I didn’t have, I didn’t have anything, I hardly even had an overnight bag with some clean underwear in. It was all just very weird. And because the children … we lived in quite a small house, still in the same house we all grew up in. My parents and my siblings had the upstairs bedrooms, so I was very much camping out in the lounge on an air bed or what have you for a couple of days and I found that quite hard. Because I didn’t sleep for about three days; I just laid on the bed watching the clock ticking and just your brain just goes around, and around, and around, and around, so many different things. You’re just wondering stuff and thinking about stuff and totally dumbstruck with stuff, and just sleeping and eating just aren’t important. You’re just literally “Urgh,” zombified or whatever, just in a total state of not human-ness. It was all very weird.

But my family were good, although I couldn’t – I didn’t want to stay there for too long. Eventually my housemates brought my car to me and I had my independence back. And that was good to put the roof down on the car and just go out for some drives and blow the cobwebs away with some music pumping and just try and, try and make my body feel something, you know, and just put a bit of … And it didn’t come. For long time, but nonetheless it was still fun driving round like a loon for a bit. Um … and then a few days after the accident, Sarah had gone already from Liverpool down to Cornwall, because she lived in Cornwall with James except when she was at university, so they had a house together in Falmouth, so she’d gone there because James didn’t live on board anymore, he had lived in their house. And so she went to Cornwall and obviously all the other partners of all the other people were in Cornwall because a lot of them were married men with wives and children who lived down there, who had already made the move down there. Marc was probably one of the only ones that hadn’t fully settled in the area and bought his own property and stuff. So everyone was down there, and there was this – I had this real sense of being drawn there. So I got in the car and drove myself there and that’s when I stayed in his little cabin for a couple of days, stayed in his room. I took his sister down with me and his parents came down and we sort of hung out there for a few days, and I stayed for a bit. Stayed with Sarah. I can’t remember after that. I can’t remember how long it took me before I came back again. I didn’t go back to my parents after that. But everyone was great, everyone looked after me.

I even sent an email out on the Sunday night, so Marc died on the Saturday morning, and on Sunday night … because I still worked at the big company that I mentioned earlier, so I’d been working there for eight years. I’d worked in the HR and training team. Everyone knew me and I knew everyone and you know, I was very involved in doing people’s inductions and welcoming new employees and keeping people well trained and up-to-speed with all the skills and whatnot that they needed to do their jobs. I was well aware that I lived with work colleagues, all of my housemates that I was moving out from, were all work colleagues, and I was aware there was going to be an impact of them going back to work on the Monday morning and essentially talking about what had happened at the weekend. And I didn’t want it to be their news to share and I didn’t want them to … It was such a big company, there was at least a thousand or so people who worked in this new building that we’d relocated to in Surrey. I was so aware that I just didn’t want to be the subject of gossip and to not clarify the facts for myself. And I knew I wasn’t going to work, there was absolutely no doubt in my mind that I was not going to work. But I didn’t want to be the subject of gossip so I remember sitting, this was before I went to Cornwall, I sat on my parents’ stairs, connected to the dial-up Internet connection and I wrote an email to everyone that I could think of that knew me and who knew Marc. And people knew him because he’d been to Christmas parties, he’d been to office events with my firm, so people knew him as my partner and knew he was in the military. He’d come to Christmas parties in this full military uniform so people knew this stuff, and I just didn’t want it to be like … . We had this little coffee bar, and I just didn’t want it to be a rumour, an unconfirmed rumour, and it had yet to break the news in terms of – everyone knew there was an accident and people had died, but the names of those people hadn’t been released yet. And I just didn’t want it to be a big rumour and a big deal for my housemates to have to share all this quite major news. So I wrote an email to all the people I could think of email who either knew me, or knew Marc, or knew both of us just sort of saying quite factually what had happened, and the fact that I didn’t want him or me to be the subject of office gossip, so here I am clarifying the facts, and the fact that it hadn’t been in the press so, you know, this email was for them and them only. And I wrote this really lovely thing at the end, which I don’t quite know where it came from or how I managed to think of it so soon, but I just said at the bottom, you know, “What I find comforting, if anything, in this horrible situation is the fact I spoke to him about …” I was one of the last people he spoke to other than the people he was flying with before he died. And we had a real lovely ending to our last conversation, lots of ‘love you, love you, love you, love you’ until you hang up. I took real warmth and comfort from the fact that yes. He’d died, but he died doing a job he really enjoyed and he died a few hours after being told just how much he was loved. And we were in a really good place – we were planning our wedding, planning our future; I was sending him property details and things for everything for when we, when we got together after the deployment.

So I wrote in the email, “Marc knew how much he was loved in the moment that he died,” and I can’t say it without crying, and I still can’t say it without crying. [Sobs]. But I said to the people in the thing, you know, “If there’s someone that you love, you have to tell them today. You have to tell them, and don’t just tell them, show them.” You know? Like. “Life is too bloody short, as we’ve found out to not tell these people that you love them.” That was my parting comment to them on my email: “Go home and tell the person you love that you love them because you never know when it’s going to be the last phone call or the last whatever.” Because yes, he was in a war zone, yes he was in the military, but he wasn’t ground troops, he wasn’t on the ground with, you know, whatever. As far as he was concerned, he was in one of the safest places you could be, and so you just never know. You just never know when your number’s up. So. And the outpouring of support I got off after sending that email … It was almost like people needed permission to contact you when you’re bereaves, and what I’d done by sending that email, unknowingly, was I’d given them permission to write back. So I’d got, and this was before the days of Facebook and all these social media things, or if it was there, people weren’t using it.

And I just got an absolute outpouring of love and comments and flowers and visitors and … Because I’d said in the email, you know, I’m a people person, I really am. I do love a good old chat and I love being with other people. I am not that great in my own company. And I’d said to them, you know, “I’m a people person and I need people now. I can’t face this alone, so if you’re in the area and you feel like calling into my mum and dad’s for a cup of tea, I might not be saying very much but please come.” And the number of people, people I hadn’t worked with for years, random friends and colleagues, and neighbours that just called in, just dropped in to sit with me for 10 minutes. They didn’t – half of them didn’t say anything or if they did, they just said how sorry they were, and I asked them not to say that, and then that was that. And you don’t forget that, even like we’re 15 and a half years post that now, and I still remember the people that came and sat with me in my mum’s front room, and the little things that people did. Like, I remember my housemates bringing me the car, and I remember who sent me flowers and what those flowers – what those things said. And my best friend came and we just sat on the beach, just because I wanted to be near the sea, because I knew that’s where he was. So we just sat looking at the sea, in March, on the beach, on our own with no one there. Just by the water’s edge. And my best friend didn’t really … we didn’t really talk that much. Well, we probably did, probably did have a good old chat but it didn’t matter what we were saying because it’s people’s presence that was important, not what they say to you in those situations.

I was very lucky to have a wide network of friends and a very supportive organisation who – the company I worked for at the time were amazing. They didn’t expect me to go back to work. I didn’t go back to work for a long time but none of it was put down as compassionate or sick leave, all of it was … I was just paid my normal wages as if I was there. They didn’t put any pressure on me to come back. They knew he was missing, so they knew I was living on the edge of: What if he’s found? And I was constantly getting updates of where they’d been searching, where the next day’s search was going to be. It wasn’t just, “Oh, he’s dead, that’s it.” There was a lot of communication, a lot going on for many, many, many, many weeks, and people were great, people were very supportive. So I’m very lucky that I had that.

Could I ask you to clarify your situation as far as finances went, because you said that you were entitled to what he’d bequeathed to you in his will; we’ve talked about this off recording that you weren’t entitled to a War Widow’s pension?

No.

Because you weren’t married. So could we just flesh that out a little bit?

Yes. And my understanding of this has changed recently, so it is a very confusing situation. Financially, at the time, I was in a well-paid job, as I just mentioned they carried on paying me so I didn’t have many worries in terms of money. I’d just moved out of a house that was expensive into a place that was relatively cheap or next to nothing so I wasn’t particularly concerned with money. I wasn’t concerned with whether my company paid me or not, to be honest, it was the least of my problems. And it’s funny how things turn out because I had no idea at the time that I would be entitled to anything, nor was I expecting to be entitled to anything, but random things happened. So Marc paid into a couple of charities that I didn’t know anything about, I didn’t know it was a thing as I’m not military and I don’t understand some of this stuff. But there is a charity called the Royal Naval Benevolent Fund, and my understanding of it – and it is not a complete understanding at all – but its that most people who are in the Navy are offered the chance to pay into this benevolent fund, and it’s something like 50p per week or 50p a month out of your wages that just goes direct to the charity. And in the event of a death in service, any death in service is my understanding – is that the benevolent fund pay out a nominal amount to the beneficiaries.

So in the first few weeks after Marc died, I just seemed to keep getting presented with cheques, and I almost didn’t know what to do with them, and many of them didn’t go into my bank for months because I was just so confused about why people were giving me cheques. And this was where Wally was really helpful, this Petty Officer or whoever he was, because I just didn’t understand it. But because I was Marc’s partner and because I was mentioned in his will, and obviously the Navy knew that instantly because they, they had dealt with all his files on board. They had all his documentation so they handed some of this stuff over to me straight away. So I remember being at James’s funeral actually, which was on the Squadron, on the base at Culdrose, and I got called into the Commanding Officer’s office. And again, I’d been called into so many people’s offices for them to go, “Oh, I’m really sorry,” and da-da-da, “… whatever we can do to support you …” And after a while, you just start to go, “Yep, move on.” Half the time, they’re not saying anything of any interest. And this one time, my mum had come to James’s funeral with me, just my mum and I, and I got called into the CO’s office and he sat me down. And I was expecting an update about the search, because I was getting daily updates on the search, like, “We still haven’t found anything; we’ve searched in this area, this area, in this area,” and it was very methodical as you’d expect. They could show me pictures of where they searched and where they hadn’t searched, what they’d found, and bits and bobs of wreckage they had, and the pictures I would get to see. And, you know, all very graphic and some of it unnecessary. But he’d given me an update, and this was probably 3-4 post accident, or … Yeah, I don’t know when it would have been because they would have had to repatriate everyone … But anyway, it was in the weeks after the accident, but just before James’s funeral, this guy called me into his office and said, “Oh, here’s a cheque for X thousand pounds.” And I’m like, “What? What? Why …? I don’t understand, what’s this for?” And he said, “Well, Marc’s been paying into this charity and the charity has paid out.” And everyone, “You are all getting the same. Everyone is getting this cheque today.” I was like, my God. You feel very lucky, bizarrely, that you’re getting all this cash thrown at you because it is helpful when you are trying to … Yeah, I’ve just lost my partner and my future and any financial security that comes with that has just evaporated.

So there were at least two charities that paid out in that way, which was handy, but this application process I was going through with Wally was for the more longer-term benefits. So, as I understood it at the time, I was applying for widow’s status to receive widow’s benefits. But the communication of that, and even to this day when I read it, is really unclear as to what I was applying for and what I was actually receiving. So I did receive his Death in Service benefit which was paid into his estate and then I was the main beneficiary of his estate, but I also receive a pension, which I thought – have thought – for the last 14 years or more that that was a widows’ pension. But it’s only more recently when I’ve poked around in dusty corners of the admin to do with that, I’ve discovered it isn’t a widow’s pension at all and I’ve never been entitled to a widow’s pension. My understanding of it – my crude understanding – because I didn’t understand the process, and the documentation isn’t actually that clear, is that the pension I receive is Marc’s Occupational Service Pension. So it’s related to his service and his length of service and his status in the Navy, but it’s not a widow’s pension. And the reason I don’t get a widow’s pension is because we were not married, so even though I’d passed the process of a ‘long-term substantial partner’ business, that didn’t get me anything because I would have got his ‘Death in Service’ through his estate anyway.

So it is all very complicated, and actually it doesn’t matter in the scheme of things, but nonetheless, it is a pretty degrading process to have to go to, to have to prove that you are entitled to something. And then years down the line to discover, actually, that’s not what I’m entitled to at all. So I do not receive any widow’s pensions, and my understanding from having poked around a tiny bit in some corners is that I will never receive anything to do with being a widow because even though I passed the ‘long-term substantial partner’ process, I’m not a widow, and I am not willing to push it any further than that. It is what it is and that’s fine, and I am lucky to get his occupational service pension, I think, based on the fact that I’m not entitled to be a widow. So, you know, I’m grateful to have that really.

Just to clarify is that occupation pension taxable?

Yes. It is taxed at source, yes, so I don’t receive the whole thing. Half of it goes back to the taxman, which is fine. You know, its fine. I feel like that is an incredibly … lucky is the wrong word because it’s just so not lucky to have it because I’d give it back in a heartbeat. But at the time when I was – it was a nice thing to have because it just relieved the financial pressures and it meant that I had choices. So I had a choice as to whether to go back to work. It’s nowhere near … my salary at the time, it was a drop in the ocean in comparison, but at least you could – I could pay for things. I could continue to pay my car loan, for instance, and I could continue to rent a room in someone’s house. I would not be able to buy property on the back of it or anything like that, but, it was enough to keep your head above water in the times when all your financial security has kind of been ripped out from under you. Especially when I didn’t know what was going with my job at that time or if I would ever return to work. But my company were amazing, absolutely faultless in the way they handled it, and in the end, I had four months off work. I didn’t go back to work for four months. And, and they didn’t quibble that at all, they just provided support where it was needed. They paid for me to go to a bereavement counsellor. All of that was happening during work time, and it continued for a long time after Marc’s death, and that was a good thing. Luckily, I had very few financial issues anyway but if I had worked for a company that weren’t as supportive, and if I’d had four months off in any other job, I’d have been broke, you know? But because they just continued to pay me without, without going, [mimics whiney voice] “Oh, but you only get five days’ compassionate leave,” or whatever … They didn’t follow any policy, because I don’t think they felt that any policy was really applicable, so they just supported me in the best and only way they could, which was to not give me any hassle about when to come back.

But I was in regular contact with them, and I did go into the office quite a few times, and I, I won’t forget the few times I did go into the office because a few things that happened that I was a bit cross about. I mean, you’re cross about a lot of things when someone has just died, but someone had cleared my desk and had put all Marc’s pictures away. Because I had a few pictures of him and a few pictures of … because we’d taken the children – my brother and sister – to Chessington. You know when you’ve got rollercoaster pictures so there were pictures of me and him and my brother and sister on all these rollercoasters and stuff. So because he was away, I had all these pictures on my desk, and somebody … I think because probably they felt they were doing the right thing; they thought that when I came back to work I didn’t want to see all that. They had cleared it all up and put it in a box so I was like, “Er, what have you done that for?” So I made a big, a big deal of just reinstating everything to where it was, just because the person has died doesn’t mean I don’t want to see their picture. But people don’t, people don’t know what to do in those situations. People make a lot of mistakes and there’s not a lot of protocol around what to do when someone dies so young, because it doesn’t happen very much, thankfully. But yeah, I forget why we started that conversation. [Laughs] How did we get to that?

… then about how you coped with anniversaries and birthdays, is there anything you particularly do to remember Marc by?

Erm … Yes, and no. So, anyone will tell you this. There’s this quandary of what to do on the death day. Do you get really sad on the anniversary of the death? With military deaths, you’ve obviously got Remembrance Sunday as well, and because Marc died in March, there’s these three points in the year where you’ve got an anniversary of some kind. You’ve got the death day, you’ve got Remembrance Sunday and then Marc’s birthday was at the end of December so then you’ve got the birthday as well. And I remember in the early days, the firsts and the seconds are really hard, especially the second. Because in the first year your support network is still really strong and buzzing and you’re still very much at the forefront and centre of their minds. But in the second year, everyone’s getting on with their own lives, so I think it’s much harder for people to remember that you still need that support. And 15 years down the line, it’s really interesting to notice the amount of people who do or don’t remember. And it’s a very small group of people that do be bothered to send or do anything now, even if it’s just a text message or what have you. And again, you do notice who these people are – again, without judgement but you just do notice who those people are.

But Remembrance Sunday for me is a biggie because you, you can’t get away from it. Remembrance Sunday is a big thing, everyone’s wearing their poppy, you know? I wear a special poppy at that time, and the kids bought our dog a poppy for her collar, you know? Like, they, they know all about Marc and they’re really into it so they understand and we, we sometimes … I mean my husband and I have done many things over the years on Remembrance Sunday. We’ve been to the Cenotaph. We’ve kept it quiet, you know, and gone to local memorials. In our village here, we’re really lucky that there is quite an active Scouts and Beavers community and it always has a military band, and there’s always something lovely at our main war memorial up here, which is where we went this year actually. And I was always put a little cross down with Marc’s details on, because – partly because I don’t want him to be forgotten. That’s one of my main, main things is I feel like I’ve got a bit … I bear the weight of responsibility for remembering him, and I know I don’t do that on my own. I know there’s his friends and family who are doing as well, but I feel like it’s partly, mainly, my responsibility to keep talking about him. And part of the reason I think people don’t contact you after the first anniversary so much as they used to, is because they don’t want to upset you.