Christiane Kirton’s husband, John, was killed when the submarine HMS Olympus was blown up in Malta in 1942 when Christiane was just 21. She describes her early life, her jobs in domestic service and her financial difficulties bringing up two children on her own. She talks about moving from South Shields to Doncaster during the war, struggling to make ends meet, and her pride in her children and grandchildren. This interview was conducted by Nadine Muller on 25 June 2017.

Click here to download the transcript of this interview as a pdf file.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

Today is the 25th June 2017. Could you tell me your full name please?

Christiane Agnes Kirton.

Thank you very much. And your age, Chrissie?

I have to keep thinking about that … 1920.

That’s when you were born? Ok. So you’re 97. Excellent. Very impressive.

97!

I know! Nearly a century!

An old bird. [Laughter.]

I wouldn’t say that! Chrissie, what can you remember about your childhood, where were you born, where did you grow up, who were your parents? Do you want to tell me a little bit about that?

Yes. I was born in South Shields. We lived in a two-room flat. A family of about six. We had beds in the living room that we took down in the morning, and put them up at night.

So that was because the flat was so small and there were so many of you? You had to make the beds in the living room? What do you remember about your parents?

My father was gassed in the First World War and he was always poorly. I don’t think he’d ever worked. He couldn’t get his breath. When I was only little, I knew daddy was going to work, and he worked down the pit, of all places. And he never complained. He never sat in his chair moping or nothing like that. He used to cobble our shoes: sole them with leather and the last I remember is him making soles and putting them on our shoes. He was a good dad. A family dad.

What made him a good dad?

I don’t know. I think he was just that sort of that. He was a real dad. If I wanted anything I went and told him. He didn’t want you to do anything on the sly. He wanted you to be honest and open. If we’d say anything and he’d think it was out place he’d say, “Now then, now then!” [Laughter.] But we had a happy life.

Do you remember anything about your mother?

Oh yes. My mother used to take in washing in a wash house. In rain and snow. And I used to say to her, “Oh mum, why do you take in washing?” And she said, “Why do you eat bread and jam?” Ask a silly question, you get a silly answer. Which is quite true.

Do you remember anything about what you used to do as a child? What would your days look like in South Shields?

We lived at the seaside, and a lot of the time was spent down on the seafront. It had a lovely pier and lighthouse at the end. I’ve got nice memories of years ago.

My husband he came from Jarrow. That’s like a nice town from Shouth Shields.

What did you used to do down by the seafront.

I did domestic work.

Do you remember when you started working?

Fourteen. Fourteen years old.

Can you remember much about that? What was it like starting work at fourteen?

I used to go out and go do domestic … Oh and I met some women, some horrible women. They treated you like a dog, a slave. I had a hard life at work because I wasn’t taught to do anything special.

My mother had eight children … no six. She had three of each, I think, three girls and three boys. Then there was mum and dad. That was eight. I had a nice family. But we did an awful lot in the house. Mum would sooner have us round her than outside. She knew we were alright [then].

Do you remember going to school, Chrissie?

Just.

Do you remember what it was like? Do you remember where you went to school?

Yes. Laygate Lane School.

Was it good? Was it fun? Did you like it?

Oh yes. We had fun at school. I enjoyed going to school. I enjoyed that.

Did you stop going to school when you went into work at fourteen?

Fourteen yes. I was a housemaid. Doing other people’s work.

How was that?

I’d only be fourteen. And I met some women.

Do you want to tell me about them?

I don’t think I’d like to. They were horrible people.

Did they make you work hard as a girl?

You did two days work in one. They couldn’t get enough out of you.

Even though you were still a child.

Yes, I was only fourteen when I went to do domestic [work]. My dad said he didn’t want me to go working where there was money involved because he was always frightened that we’d get caught up in it, you know. So I went domestic, and I worked for some snooty-nosed people as well. Some were terrible.

When did you meet your then-future-husband for the first time?

I was seventeen. Oh now … I think I was a lot younger than that. Maybe fourteen.

Do you remember meeting him for the first time?

We all used to go round in a crowd. And we had some fun. We lived at the seaside so in the summer we spent our time down on the beach and the sea.

You don’t remember how you met your husband for the first time?

No. What I do remember is too bad to repeat.

Do you remember when you first started going out with your then-future husband? Do you remember your courtship?

Yes.

Do you remember anything about that?

I was only fourteen. He was a baker. He used to go out doing the bread, making the bread. We were so happy. I can’t complain about that. He was so nice. He was so nice to me. He respected me. Because he knew I’d been put on over the years.

I had no childhood. Fourteen when I went to do domestic work. For about four shilling a week or something like that. I know I never had money. Mind, I think it’s a good thing because I don’t worry about it now. But to think that all them years … they don’t come back … They were terribly miserable years. In my story,I think I said it was the most miserable time in my life.[1]

Because of the work?

Yes. I used to work for women … She used to say, “Do it with vinegar and water, the furniture … with a wash leather. Wipe it all down with a wash leather”. And I knew she was a funny sort of woman that I worked for. And she said, “Have you done this?”, and I said, “Yes”. I’d do it with a wash leather and vinegar in the water and cleaned it up like that. And I remember one day she got on my nerves a bit and I thought I’m not going to do anything, I’m just going to take a duster over it. She came in and said, “Have you done it with a wash leather and vinegar water?” And I said, “Yes”. And I hadn’t [done it]. And she did that with her hand, [and said] “Filthy, dirty”. And it wasn’t. I think it was the last day of the week. She’d been on every day of the week and taken her fingers and run them [along the furniture] to see if she could find some dust. Shen ever could, but she would always grumble. I didn’t have a good life when I was cleaning.

Do you remember the time just before you married your husband?

Yes.

What was it like just before you got married.

Ah, he was a gentleman.

Why? What did he do?

He was a baker, and he used to fetch me my doughnuts every morning for breakfast because he worked nights in the bakery. I had some happy times. I had some sad times. When I first got war [widows] pension, I think it was 8 shilling a week, which I had to pay my rent from. There was nothing left for food. I used to go to mum, and she used to give us money for a loaf of bread. She wouldn’t see the two children go home without anything in them. She was very kind to me. It’s too sad. I can’t do it.

Can I take you back to a happier time, Chrissie? Do you remember your wedding day?

Yes. I was only seventeen. I wrote my story, but … I forget now.

That’s ok.

It’s not a very happy one.

That’s ok, too. Not all stories are.

I don’t like to talk about it.

That’s ok. Is there anything you’d like to tell me that you feel you are able to talk about?

I never had any new clothes. All hand-me-downs because it was six of us. My mother had three of each. Three boys and three girls.

What were your siblings like? Did you get on with your siblings, with your brothers and sister?

Oh yes.

Yes? What did you get up to?

Going ‘round knocking on people’s doors and running away. We thought that was great fun. Until one day we did it at an old lady’s house … well, she wouldn’t be old because they were old when they were married and had a family … I couldn’t put an age to them … . I remember one day she did something. I don’t know, I forget. I know I threw a bucket of water over somebody. I don’t know what happened now … I’ve forgotten now.

You sound like you were a handful knocking on people’s doors and running away and throwing buckets over water over them.

If you were down and out, you were no good. Yet, my dad was a very strict dad. What he said was law.

Chrissie, do you remember how your father died?

How old?

Do you remember how he died? Why?

My mother and dad they looked after me. My pension wasn’t enough to live on. They asked for a halfpenny when they were going to school and I had all the cushions off the big settee feeling down seeing if anything dropped out of anybody’s pocket. And that was a hard time.

Chrissie when did your husband join the war?

He joined the Navy.

And that was in the Second World War?

Yes. And he was away. He moved away with the army. I brought two babies up myself. He was killed in April [1942]. And I was only 21. And I was left with two babies.

How old were your babies?

I would’ve been about twenty-one.

And how old were the children when your husband died? Were they very little?

I can’t think. I can’t think about it where they were or when I’d had them … It’s all gone. I don’t want to remember then … .

Do you remember when you heard that your husband had died?

When I was … ? When?

When your husband died. Do you remember how you heard about it? Did you get a letter? A telegram?

No, I can’t remember. I wasn’t very happy with my life. I can’t remember.

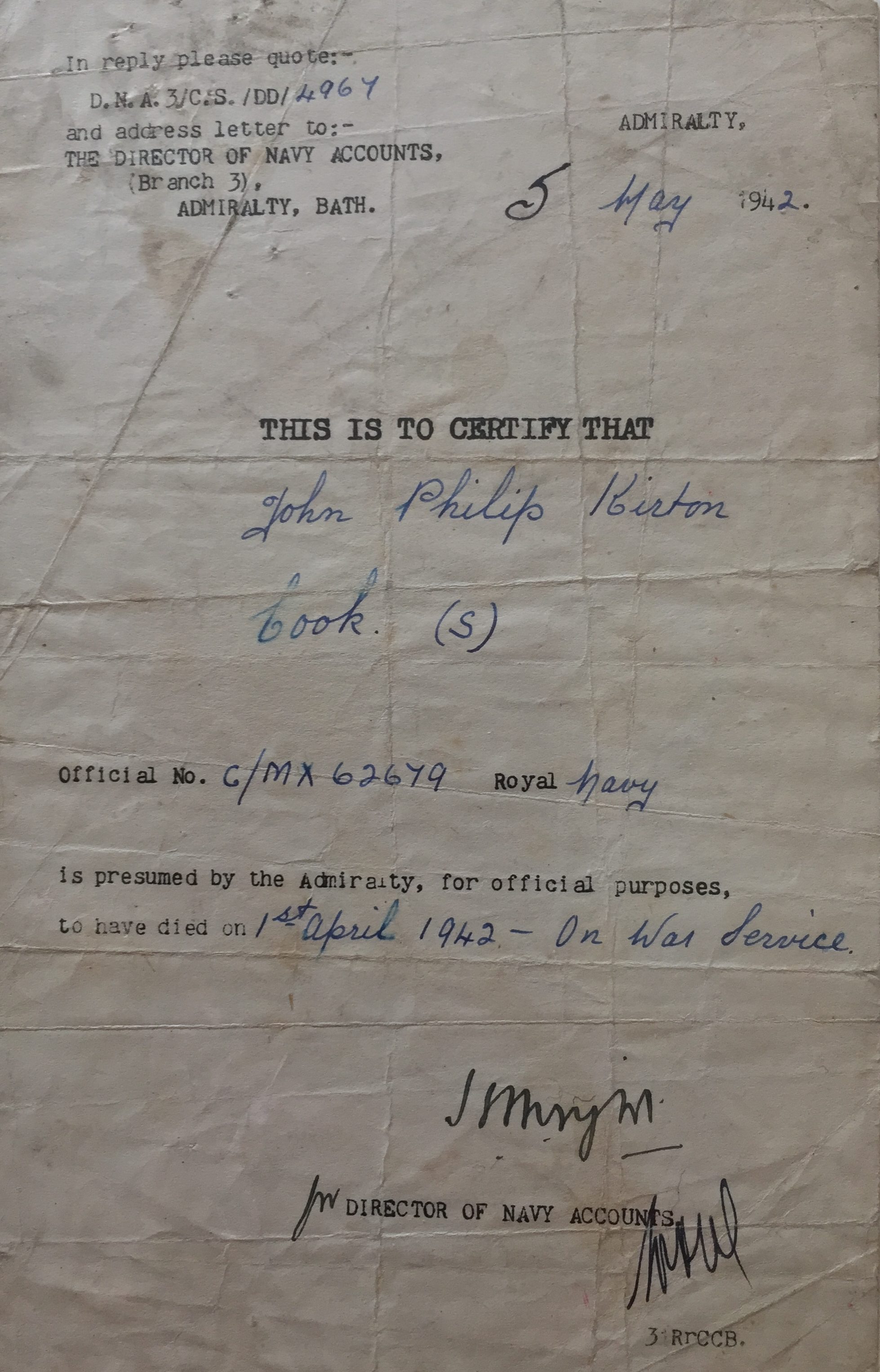

Letter by the Director of Navy Accounts to Christiane Kirton, informing her of her husband’s death. 5 May 1942.

You said your War Widows’ Pension was very small. It wasn’t enough to live on, you said.

Yes. Two babies.

Did you have to go to work?

Yes, I only knew domestic work. Wherever I got they’d all put on you and put on you. “Just do this …”, and the next week you’d go and “Would you do that?”, and in the end, you’re running the house for no extra money. They tried to get blood out of a stone. That sort of person. No matter what you did, you hadn’t done enough. And my dad was so strict. I couldn’t stand it. I was had a hard life.

Do you want to tell me a little bit about your children?

They were good children. Very, very kind. I brought them up with good manners.

So even though you had a very hard time you still did a very good job bringing gup your children.

Yes, they weren’t going to be like me.

You wanted them to have a happier childhood, yes.

If it was my last halfpenny, they could have it. Many a time I’ve sat with no money in my purse. I wouldn’t like to go back. I never had a pair of new shoes. I used to go to second-hand shops. Oh, I was hard up. I don’t want to remember now.

That’s ok. Do you want to tell me something about who your children are and what they do now? What family have you got?

Christine’s a Comptometer Operator. And my son is a … What did he do? I don’t know what he did. I forgot.

That’s ok. But they both had a good education?

Yes.

They went to school?

Oh yes, they went to school. They stayed on at school. You know from fourteen to sixteen.

They didn’t have to go to work like you?

No.

I never went anywhere. I don’t think I had any new clothes until my children grew up.

I had a terrible bringing up … My mum couldn’t help me because she had I think three boys and two girls after me. I forget all about what I’ve done and what I haven’t done. Or at least I must want to forget. It was so bad.

So some of the happy things you’ve talked about was that your husband was clearly very kind to you?

Oh very. He was a baker.

He sounds like a great man.

He used to bring me two doughnuts every morning from the bakery.

Did he spoil you?

Yes.

Yes? Deservedly so. You deserved to be spoiled, didn’t you.

He really loved me.

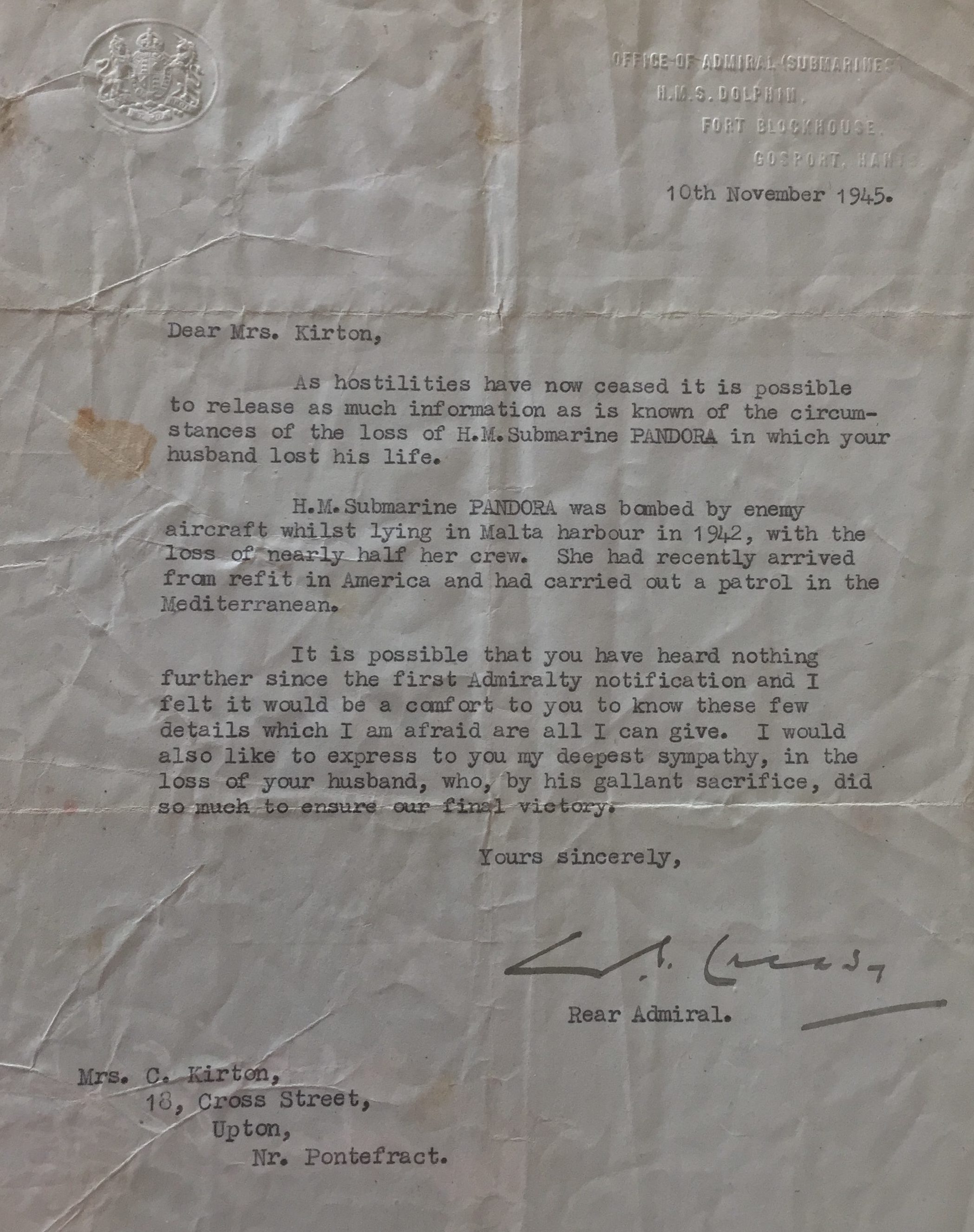

Letter notifying Christiane of the details of her husband’s death. 10 November 1945.

Do you like going back to South Shields?

No, I don’t. I like Yorkshire best.

[Laughter.] You’re an adopted Yorkshire woman now. A Geordie in Yorkshire.

A Geordie Yorkshireman. [Laughter.]

Do you want to tell me a little bit about what life is like now?

It’s now much better. [Laughter]

Well, you live in a beautiful care home everyone seems very chipper and smiley and happy.

Yes, it’s lovely.

It’s in beautiful countryside.

That’s what I love.

You love the countryside?

Yes, because mine was the seaside. South Shields, right on the coast.

So you’re not much of a city girl?

No.

Neither am I.

Are you not?

No, I live in Derbyshire. The Peak District.

Oh, the Peak District!

Yes, all in the hills. With my dogs.

It’s lovely.

It is.

I came to Yorkshire …

When did you come to Yorkshire?

My daughter was about … She’d only be a baby, I think. The little boy would be four.

Why did you come here?

I was evacuated.

Ah ok. What was it like being evacuated?

That was lovely living in the country.

So you were evacuated because of the war, but you actually quite liked where you went?

I loved it.

So it wasn’t a bad thing necessarily?

No.

Chrissie, you’ve said that your life hasn’t been a happy one, certainly not during your childhood …

The best years of my life was when I got married.

The happiest?

And I had children. Babies.

How do you feel about life now, Chrissie?

I think it’s treated me rough. I’ve got nothing to gloat about. I’ve had to work all my childhood. I’ve worked for some horrible, horrible people. They thought they could get blood out of a stone. No help at all. Not like they get today. I don’t like talking about it, that’s why I forget where I was.

I’ve got a really good family.

Yes? That’s something to be proud of, isn’t it?

It is. And what I couldn’t have, they’ve got. I’m quite happy about that.

Yes that’s a credit to you, isn’t it? And they got that because of you. Because of your hard work.

Oh yes. My son and daughter, they think the world of mum.

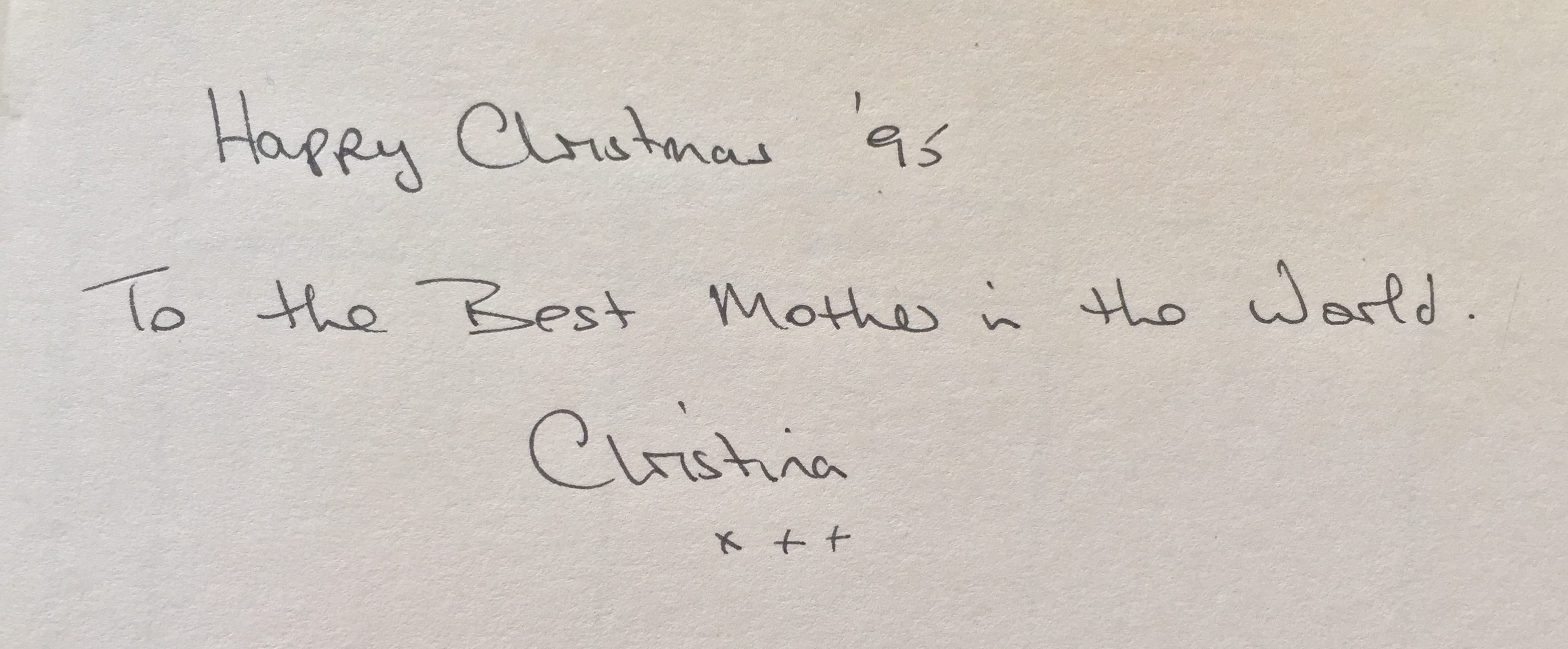

Dedication in a photo album of Christiane’s life that was given to her by her daughter, Christina Claypole, for Christmas 1995.

I can tell. They love you very much, don’t they? They think you’re very special. That’s what your daughter said earlier, didn’t she? She said, “This is a very special woman”. That must be lovely to hear your children say that, to know that they appreciate you?

Yes. Talk about the best years of your life. I lost mine. But I’ve always gone out and done charring. It’s all I knew. I’ve sat from Saturday to Monday, all the weekend, not a halfpenny in my purse. No money. Hoping the bread would last out until I got my pension on Monday morning. It wasn’t a very nice life.

No.

[1] Interviewer clarification: Christiane had written down her life story by hand some time before this interview and refers to it throughout as “my story”.

This interview transcript, its print and online versions, and the corresponding audio files are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives Licence. This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as the work in question is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to War Widows’ Stories. If you wish to use this work in ways not covered under this licence, you must request permission. To do so, and for any other questions about this interview, how you may use it, or about the project, please contact Dr Nadine Muller via email (info@warwidowsstories.org.uk), or by post at the following addressing: John Foster Building, Liverpool John Moores University, 80-98 Mount Pleasant, Liverpool, L3 5UZ.