Rev. Richard Cobbold published Mary Anne Wellington: The Soldier’s Daughter, Wife and Widow (1846) in the hope of raising funds for his subject: a widow who had accompanied her husband on all his postings, and who, after his death, had fallen on hard times. In this biography of Mary Anne, Cobbold covers her childhood as a soldier’s daughter, her travels and adventures as a soldier’s wife, and her struggles as a soldier’s widow. Although Cobbold’s aim to raise money for Mary Anne meant that he was clearly predisposed to paint a favourable picture of his subject, his account of her widowhood provides thoughtful impressions of the challenges destitute war widows faced in the mid-nineteenth century. The biography tells of Mary Anne’s life as the daughter of a soldier, of her travels with her husband on his postings abroad, and of her life as his destitute widow.

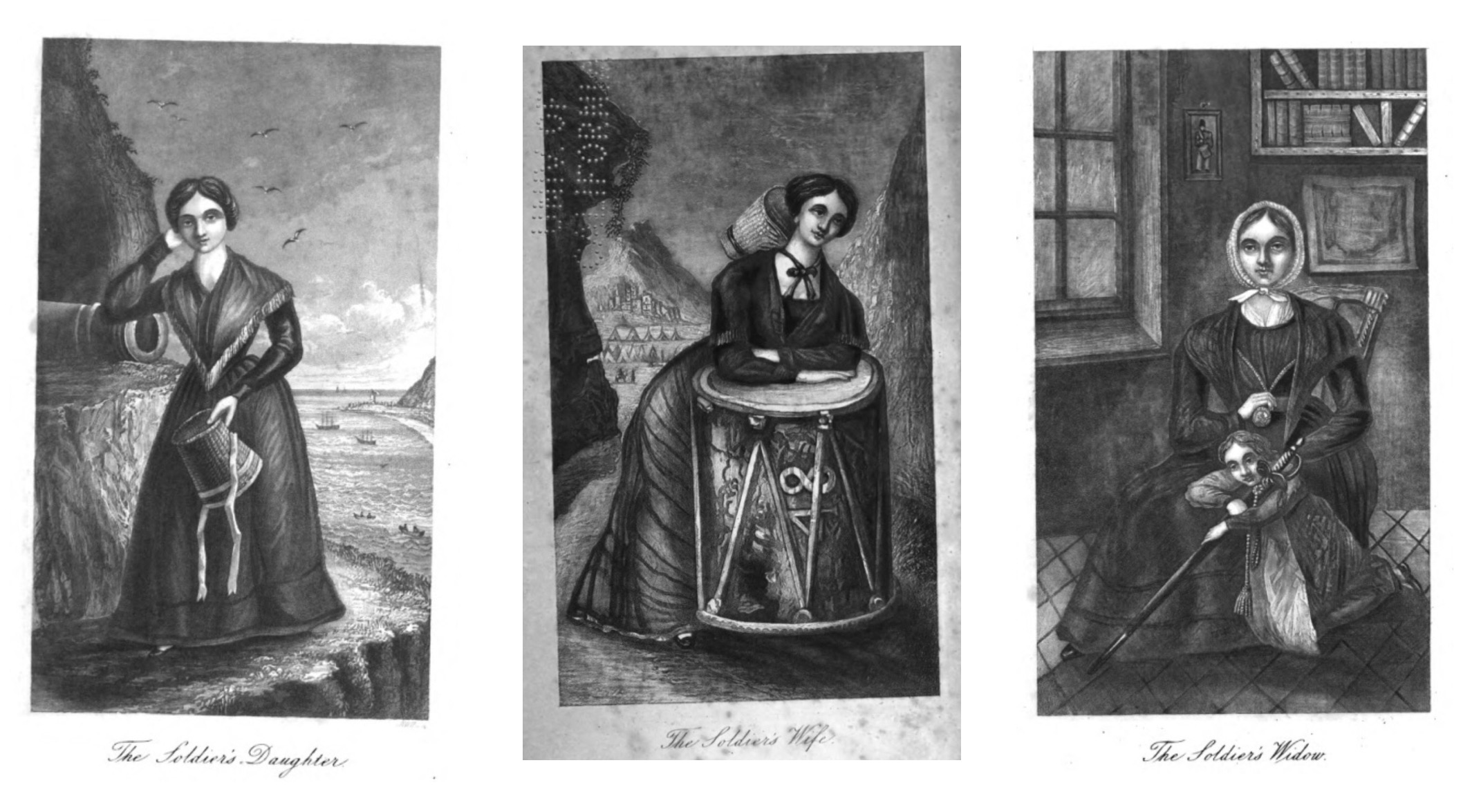

These are frontis pieces to each of the three volumes of Cobbold’s biography, showing Mary Anne Wellington as a soldier’s daughter, a soldier’s wife, and a soldier’s widow respectively. © University of California

‘What is your name? Where do you live? What age are you? How many children have you? What are your earnings? What do your children earn? How long have you been a widow? Have you any pension? Have you no means of subsistence? Are you able-bodied? Have you no friends? To what parish did your husband belong? How come you to be so reduced? Cannot you do something for a livelihood? Are you quite destitute?’

These are some of the questions Mary Anne Wellington, an army officer’s widow, was asked when applying for assistance to her local Board of Guardians, according to Cobbold’s account of her life. He points out that while the journey to the Board of Guardians meeting was not a long one for Mary Anne Wellington, it could well be a burden to those who had to travel greater distances, though ‘the liberal inventors of the New Poor Law think that there is no kind of hardship whatever in poor people coming before the Board’. But ‘who’, he asks,

has not seen aged females tramping through the mire and snow, through wind and rain, in the bleakest weather, to apply to the Board of Guardians for relief? There they sit, in one common room, with wet shoes and stockings, and clothes drenched through, awaiting the summons of the officer to go before the Board.

The destitute widow travelling alone, wet through and through, undoubtedly would have stirred the feelings – and sense of propriety – of the middle and upper classes, as would the scenes Cobbold goes on to describe. A woman without a male guardian, made nervous by the prospect of having to enter and answer to a room full of men, as though she was a defendant in court. Even though Cobbold highlights the gentle conduct of this particular committee there is no doubt that he objects to this treatment of the widow:

She entered, with a heart beating violently, and limbs trembling till they knocked one against the other. As she entered, every eye beheld a tall, straight person, in deep mourning, with a countenance that spoke much sorrow, but with an air of past independence […] The poor woman stood before the Chairman, Vice-Chairman, and a numerous body of Guardians, the Clerk of the Board, the Relieving Officers, and the Governor of the House; and had to answer publicly any question which any man there present chose to put to her. Severe, sometimes, are the cross-examinations which applicant has to undergo; and not always in the gentlest terms; for there sit too often accuser, judge, and jury, and the poor creature has but little chance of escaping the utmost rigour of the law. Such, however, was not the case with the Board before which the soldier’s widow stood, though to her terrified vision it might appear as if she stood before it like a criminal.

The New Poor Law, according to Benjamin Disraeli, ‘announces to the world that in England poverty is a crime’, and Mary Anne Wellington, like many others, had to defend herself in order to receive the assistance she desperately needed. Cobbold’s tone is critical when he evokes the comparison between poverty and crime, and he openly questions the usefulness of a law that is designed to minimise rather than provide support to the poor. ‘In country parishes’, he writes, ‘who are the the administrators of this law but men for the most part deeply interested in keeping down the relief as low as they can?’

For Mary Anne, her appearance before the Board of Guardians is more terrifying than any of the scenes of war she has witnessed in her time as a soldier’s wife: ‘I have been in most of the Peninsular battles with my husband, and have stood with the soldiers of my country in the face of England’s bitterest and most formidable enemies; but I never knew what fear was till this moment’.

Like the vast majority of widows, the first expenses with which Mary Anne was faced after her husband’s death were those incurred by the adherence to Victorian mourning rituals. A funeral as well as mourning clothes for herself and her daughters had to be paid, and this necessitated the sale of Mary Anne’s belongings: ‘when the few things which a poor widow has are parted with, and the bills for her husband’s funeral, and her own and her daughters’ plain black gowns, are paid, there remains but a small surplus, if any, to provide bread for the week’.

According to Cobbold, Mary Anne Wellington’s pension ran out soon after her husband’s death, her other resources having been spent on the funeral and her own and her daughters’ mourning costumes. The source of this pension is not mentioned in Cobbold’s account, and armed forces widows’ pensions operated under inconsistent rules.

Mary Anne Wellington was able to benefit from the charity of some wealthy benefactors. After her outdoor relief was granted by the Board of Guardians, the Chairman assured the widow he would make her case known in Westminster. As a consequence, Cobbold writes, ‘exaggerated statements got into the papers, and her sons saw, in the London journals, a long and erroneous account of their mother’s life. She was persuaded, however, to apply to Her Majesty, to the Queen Dowager, and to the Duke of Wellington […] and after strict inquiry into her case […] the result was favourable to her application’.

Yet, the relief this act of charity provided was temporary: ‘these donations, for a time, greatly assisted the soldier’s widow, but they could not provide for her beyond a certain time’. Mary Anne once again had to apply to the Board of Guardians for renewed outdoor relief, and ‘three shillings weekly were again allowed’.

Private charity, of course, was a temporary relief only available to those who had an influential champion willing to bring their case to public attention and whose husbands had either enjoyed some form of esteem in their lifetime or had left them in circumstances dramatic enough to incite pity and outrage.

According to Morgan George Watkins, Mary Anne Wellington eventually ‘was placed in an almshouse by Cobbold’s exertions’, after his account of the widow’s life and fate ‘brought in no less than 600l’. Though a steady and safe existence, it is nothing short of depressing to think that a woman who had dedicated the largest part of her life to her husband’s service for their country had to spend her widowhood uncertain of her future, and live out her days in an almshouse.

Alas, this image of destitute war widows is one we encounter again and again over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. You can read Mary Anne Wellington as a free e-book here, including its original illustrations. If you’d like to know more about war widows in the nineteenth century, you can take a look at our History pages.

Sands, Anthony; Mary Anne Wellington (b.1789); Northampton Museums & Art Gallery; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/mary-anne-wellington-b-1789-49983