Sylvia Elliott talks about her childhood in Derby during the Second World War and about meeting her husband. Bill, who had been badly injured in Korea. She describes her forty-year marriage to Bill, their two daughters, Carol and Dawn, and his commitment to the British Legion. Sylvia outlines her life since Bill’s death, including moving to Skegness, travelling around the world, and marrying again to her second husband, John. Sylvia also details the difficulties she encountered applying for a War Widow’s Pension. Conducted by Mrs Glenda Spacey on 10 May 2017 in the company of Nadine Muller.

Click here to download the transcript of this interview as a pdf file.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

Can you tell me your name please and how old you are?

Sylvia, Sylvia Elliott. Now, I was Sylvia Betesta when I was a child. I’m 84 now, and I was born in Derby of a very big family. There was nine of us, and we used to fight like anything. I don’t remember an awful lot about when I was small, but when I was six, when war broke out, we were all put on buses, all lined up and put on buses with a label on us and sent off. I went to a little place called Stanley Common, just outside Derby, but as a child of six I thought that I’d gone hundreds of miles away and I thought my parents had given me away because nobody told us anything.

We had to sit in a school room and they came and picked out who they wanted, and I went to a nice couple and they were very nice. As I lived in a town I didn’t know lots of things and this gentleman where I went to live had got a greenhouse with tomatoes in it and he let me pick one and I’d never picked a tomato in my life. Those little things … We went skating, well without skates, on the pond that was there. Then he was taken ill and I know, from afterwards, that he had to go in hospital, so I was sent somewhere else and my mind is blank from there. I didn’t remember anything.

I don’t know what happened, something must have done, but anyway the next I remember is being back home and the war was on, and my grandma used to sit … when the sirens went … she used to take me and we’d sit on the cellar steps and she made a cup of cocoa. One night, my sister – my oldest sister was in the WAAFs [Women’s Auxiliary Air Force] – she was home on leave and she said, “I’m not getting up again for the sirens”. So, anyway, the sirens went and as in all the houses where I lived, there’s a tin bath at the bottom, hanging on the wall, and a bomb dropped four doors away from us. The bath fell off the wall, and my sister fell out of bed and fell all the way down on the stairs. I remember all that, but I don’t remember much more until … I must have been a bit older and my father had been in the Army, but he was at Nottingham Castle guarding all the ammunition in the dungeons at Nottingham Castle, and he and his friend were supposed to guard it.

Then, the next I remember is him being at home again, and I must have been a bit older, quite a bit older, and he fetched me out of the house one night. Oh, he was a fire watcher then, ARP [Air Raid Precaution] man, and he fetched me out and he said, “Come and look”. There was a storm on and we watched, and he said, “Look up in the sky”. And there was this tiny red light and he said, “Keep watching”. And then it burst into flames. It was the barrage balloons and the lightning was striking them and it was just like fireworks up in the sky. They couldn’t get them in quick enough, you see, to save the balloons. They had one balloon, it was called Big Bertha, on the arboretum, right near where we lived. And where we lived, we were right at the top of the street and exactly across the road was Derby Crown China Works. We found out afterwards that that’s what the Germans were trying to bomb, as well as Rolls Royce and the Midlands Station where the trains were being built.

Later on, when they were coming off duty at Rolls Royce … the shifts used to change, they used to pass in the road, the night shifts and the day shifts, they used to pass each other as they were changing shifts … and two German aircraft came in and machine gunned them and there were hundreds of them dead. From there on, they changed the way they did the shifts, so there weren’t two lots. One of the German planes was shot down, and inside it they found a holiday brochure, and it had this map, and it had Rolls Royce ringed in red, Derby Crown China Works [The Royal Crown Derby Porcelain Company] in red, and the Midlands Station in red. So that’s what those two German planes had come over with, that’s all they’d got to follow. If I’m saying Derby Crown China, that was how we knew it. It’s really Derby … oh, I can’t remember the real name as it was then, but we called it that.

My brother worked there and we were only across the road from it, and they used to have a siren that used to go. This was after the war and the siren went to tell them they’ve got five minutes to get into work. This siren went, my brother jumped out of bed, ran down the stairs, cleaned his teeth, ran out across the road, and his foreman had a cup of tea waiting for him.

As I got older, I used to love to go to church, and I loved Brownies, and then I was in Guides, and I was in a carnival band as a pace stick girl at the front. Best in the Midlands we were at one time. We used to go into competitions and all things like that. Then we used to go to a dance and this was when I was seventeen / eighteen-ish, at two dance halls, The Ritz and The Rialto, and they used to let [Armed] Forces go in free, so, of course, we girls used to go to the dance because there were lots of Forces. One day, I went and I saw this soldier sitting there, and he never danced, and I went and sat talking to him. I said, “Why aren’t you dancing?” And he said, “Oh, I can’t”. He said, “I’m convalescing, I’ve been in Korea”. And he was back in Normanton Barracks, which was where the Sherwood Foresters were, and that’s how I met my husband.

He was in the Sherwood Foresters, and then he was sent to Germany in the Sherwood Foresters. He was on duty at the Nuremburg Trials. They could only do one day at a time and then they sent them on … R&A I think they call it … something like that … . He was telling me all about that, and he said he’d been wounded in Korea. They’d gone into a trap and the whole platoon was wiped out. Oh, I’m taking you too far, that was what my husband was telling me. Husband-to-be was telling me. He was found in the jungle after two days. There was only him and his friend who survived. His friend had both legs blown off, and my husband-to-be had his legs badly smashed up. They were brought out of the jungle on stretchers, hanging under helicopters.

He was taken to the MASH, the American MASH, and he said it was exactly the same as on the TV. He was in there, and they said the Americans saved his legs, but if he’d have been taken to the British one, they’d have amputated. They were that bad. While he was in the MASH station, he said the operating tables were just like it is on the TV, everything was exactly the same. And he said this officer came round when they were all in their beds, a high-up officer, and he got a purple cushion and he was giving them all the Purple Hearts, the Americans, and he gave my husband-to-be one and he said, “I don’t want that. I’m British”. And he gave it him back.

So, now I’ll tell you about what he told us about when he went to Korea. He was in Germany with the Sherwood Foresters, and he was seconded into the Northumberland Fusiliers and sent to Korea. At the time, my husband was only seventeen, I think, and they were the first ones to arrive in where the fighting was, and the Americans. They had to wade through the Imjin River, and then they went into the jungle and my husband said it was awful, it was horrific. He said the Koreans, the North Koreans, never left bodies intact, and he said you only knew whether it was British or American that you were crawling over by the colour of the uniforms. He wouldn’t ever tell me much about Korea, he said it was too horrific, and none of the men that went to Korea at the same time as my husband … They joined the Korean Veterans, and they used to sit talking, and they talked together, but they wouldn’t ever let me listen.

Commemorative doll given to William Plowman aboard the ship that transported him back to England after he had been Injured in Korea. C. 1940s.

Then, after they moved him from the MASH hospital … I’m not sure, I think he was taken to a hospital in Hong Kong and he was there for a long, long time. Not quite sure how long. When he finally came back to England, him and his friend were on a bed on the decks of a cruise ship, a very posh cruise ship, he said, and they all spoiled him silly, all the people on the ship. He was 21 when he was coming back on this ship, and the nurses, I’m not sure whether it was the nurse or the staff, made him or gave him a little sailor with the name of the ship on. Then he came back and he was sent back to Normanton Barracks to recuperate, but his mother didn’t know he’d been wounded. They’d [his family] gone to the cinema and they’d seen these helicopters coming out of the jungle with the stretchers hanging below, and she said that she didn’t know that one of them was her son. She had to get in touch with one of the ministers and they got in touch with London to find out what had happened, and then she was told that he’d been wounded in action. Then I met him whilst he was at Normanton Barracks.

Is that in Derby?

In Derby. And then he started taking me home to his house, and he lived at B-Winning, between Alfreton and Chesterfield. I was one of a family of nine children, and in the war we had hardly anything, living in a town. When my husband to be took me to his mother’s, they had everything, living in the country. They treated me like a princess. It was lovely. I think I fell in love with the family as well as my husband-to-be.

He was demobbed. He was still in the Army but he couldn’t stay in because he’d been wounded but, at the time, he didn’t know that if he’d have been disabled out of the Army, he would have had a green card and he would have never been out of work. But some kind person told him that if he took it, he would never get a job. There was no counselling in those days and he came out, he had no job, no career because he’d gone in the Army to make it a career, and he had to do labouring jobs as time went by. He had to travel the country, so he was never with me. Well he was sometimes. I had two girls, Carol and Dawn and we had to live from hand to mouth on what we got.

Seventeen years after, we were at a Korean Veterans’ meeting and the limbless man was there, and he said, “Oh, Bill, I bet you get full pension”. And Bill said, “I don’t get a pension”. And he [the man] was very angry, and he got some forms out of his case, filled them in, sent them away, and by return post my husband got a full pension. When he asked about the back money, they said, “No, because that’s your own fault for not asking”.

How old were you when you married? Can you just tell me a little bit about you and your husband when you first got married?

I was twenty when I got married and my husband would be about,23, I think. I didn’t know anything. In those days, your parents never told you anything. So, of course, as soon as we married, I got caught for a baby. So, I had my first wedding anniversary in hospital and Carol was born two days after my first wedding anniversary. We had a very hard time up until then and then my husband, after a long time, he did manage to get a job at Rolls Royce in the Despatch Department. By then our girls were growing up and I was working at Rolls Royce as well, in the offices. But, he used to be the last one to touch an engine when it went to go on the plane, into a carrier plane, to go to America or wherever. I used to buy all the nuts and bolts to build the engines.

We were married for forty years and we had a fortieth anniversary party. My son-in-law was a fantastic master chef so he did us a big party. My husband, his life revolved around the British Legion and we had the party at the British Legion and we had this party on the Saturday night and on the Sunday was our Ruby Wedding day and we had an open day. We went to the Legion in the evening and walked home and he went to the toilet and he never came back, he had a massive heart attack and that was on the day of our Ruby Wedding.

All the time you were married, were you always living in Derby, or had you been together somewhere else?

No, always in Derby. For the last part, when my husband had retired, we lived on the War Memorial Village at Derby. The people of Derby had made a little village for the ex-servicemen that were wounded and our house was called “Anzio”. They were all named after battles. Before our Ruby Wedding, of course, the Korean government got in touch and said that all those that were in Korea and wounded, they would go as a guest to Korea but my husband, the doctor wouldn’t let him go. He said he wasn’t well enough because he was having lots of pain with his legs and he was having mild heart attacks, so, he said he couldn’t go.

So, after a while, one of the men from Nottingham said, “They’ve sent Bill’s citation from Korea”. And I’ve got it and the Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire wants to present it to him. Well, Bill was very, held himself to himself, never showed his feelings, in fact, that was what caused any problems between us. I used to say to him, because he never showed his affection, and I used to say, “Haven’t you got any feelings?” And he said, “I left them in Korea”. And I knew he wouldn’t go to a proper presentation. It was Colonel Hilton, the Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire and he was the President of the Royal British Legion, as well, at the time.

So, they said, “Well he wants to present him properly”. So, I said, “Well, the only place he can get him is the British Legion”. So, we had a bit of a cloak and dagger between us with the Nottingham Korean Vets and Colonel Hilton and myself. I said we used to go every Saturday and Sunday evening and Wednesday and Colonel Hilton had rung me up a few times and he said, “Can we make it and I will come to the British Legion to present him in front of everybody?” So, I said, “Well, I’ll try and get him one night when he’s not on duty”. Because they used to take it in turns, the committee, take it in turns to be on duty. We had a couple of games of bingo as normal and dancing and artists sometimes. So, they would announce it and look after everybody.

Anyway, this Sunday, I said, “He won’t be on duty”. So, when we were getting ready to go that was all arranged, and they were going to hide in the bar, all of them, including Colonel Hilton. We were getting ready and he said, “Oh, I think I’ll put my old sports coat on tonight”. And I said, “Oh, no. I always get dressed up when I go out on a Sunday night, why can’t you, just for once, please me”. So he put his suit on. When we got there, he was like a jack in a box, and I kept saying, “Sit still. Sit still”. And he said, “I’m sure I’ve seen one of my friends in the bar from Nottingham”. And I said, “No, you haven’t. Sit still”. And I kept thinking, “Oh, please hurry up and start”.

Anyway, then they started and Colonel Hilton came through the door and all the Nottingham veterans came behind him. I’m getting a bit full up now. They all walked up to the dance floor, and he sat there and he was dumbstruck. Colonel Hilton said a few words, and then his friend from Nottingham stood up and he said, “And now we’re going to do a ‘Bill Plowman: This is Your Life’”. And they went all through Bill’s life, and then they talked about Korea, what he’d done in Korea, and how he’d been wounded. I’m sorry, I’ll have to stop a minute.

[NM] It’s ok, we can just take a break. I’ll pause the recording for now.

So, we were talking about the presentation.

Yes, and you could tell what he was like and nobody knew. Although he had a very bad limp, nobody, only the Korean vets knew that he had been wounded. So, they did this ‘This is Your Life’ and one had made a book of his life, but I couldn’t get hold of that because it’s up at the top the cupboard. Afterwards, all the women in the Legion and they’d be about 150, came up round him crying and they were all saying, “We didn’t know you’d been wounded, Bill”. Nobody knew anything about it.

Then he got quite grumpy in his old age. He had to retire through ill health and when he retired. You can tell how everybody thought such a lot of him. When he left Rolls Royce, they had a party for him at our Legion and somebody else did a book about his life. Loads of people came from Rolls Royce to see him and then that was when he retired. As I say, he got rather grumpy and he didn’t want me to work when he’d retired. He was one of the old type and he said, “A man is supposed to look after his wife and family”. And he kept on and on at me to retire.

Were you still at Rolls Royce?

I was still at Rolls Royce and he kept on at me to retire. It was only two years before I would retire. So, in the end, he wore me down and I retired and I lost ever such a lot of money through that, but the thing was I retired two years before my birthday, when it was 60 then, and I retired at 58. We had that time together, and Bill died in the November as I would have officially retired the following April.

How old was he then?

He was 60. So, he’d be about 60, I think he was. And so if I hadn’t had retired, I would have never forgiven myself. When it was his funeral, I said, well my daughters, especially my oldest daughter, they’d just gone back from the party because they were living here then. They’d stayed with us until the Sunday and they’d gone back Sunday tea-time, come back here. I had to ring her and tell her that her dad had died, and she wanted just our family funeral. Anyway, when it came to the funeral, it was unbelievable, there was all the standards, Korean Veterans’ standards from round the country. There were about five British Legion standards, there was the Women’s Section’s standard and, I can’t remember his name, who was Bill’s Commanding Officer in Korea. Colonel Hennington Booth. I can put that right for you, in a little while, I’ve got it in some notes. And he was there and he spoke at the service.

And this church, it was a great big church at Derby, on our village, it was a great big one, and it was full to overflowing. All the directors that knew me and Bill at Rolls Royce came, and all my … I dealt with a lot of companies, I had to go round to the companies … and two or three from every one of the companies were at the funeral. So, he was a very loved man but the thing was, he dedicated his whole life, after he came out of the Army, to the Royal British Legion, and I think that’s it..

Can I ask you: so how did you end up living here now? What happened after your husband died?

When he died in the November … Oh, one thing I forgot, he’d only just, in the July, decided to have a car because they take the pension and he had a car, that was the July. I’d got a car because I was working before I retired but when I retired, I sold my car, so we’d just got the car Bill had got from … the disabled car. This was July and he died in the November. The day after he died, they fetched his car back and I’d got no transport at all. Anyway, I said to my daughter … I’ll tell you a funny feeling I had. When we belonged to the Legion, everybody was our friends. Well, when Bill died, I felt that, and it was a very strange feeling, I hadn’t got any friends, they only wanted to know me when Bill was alive. I had the feeling that the women thought I was going to go after their husbands. No way would I have done that, but that was the feeling I got, and there were only two or three that stuck by me. And friends that we’d gone away with, she was one of the worst. She sort of ignored me.

So, I’d always said that I’d love to come and live down here, and I said to Carol, one day, in passing … She came a lot to see me. This is my eldest daughter, Carol. I said to her, “Will you look if there’s any little bungalows to rent?” So, the following week, she said, “Oh, mum, I’ve been told of one but you’ve got to come quick and have a look”. So, one friend that I had kept, that had stuck by me, I said to her, “Would you and your fella nip me over?” So, I came over, had a look, and I said, “Oh, it’s lovely”. And Carol said, “Well, you’ve got to tell him by next week”. So, I said, “Alright, I’ll have it”. So, I went home and sorted everything out and everybody said, “You’re going too quick. You’re doing the wrong thing”.

Well, my doctor, and in those days the doctor came to see you and, actually, I think he felt a bit guilty over Bill’s dying like that. He told me he never expected him to have that heart attack. So, he came to see me, to check I was alright and how I was getting on. I told him [that I was moving away], and he said, “I think it’s the best thing you can do, you go”. So that’s how I came. I just upped and came to Chapel St Leonards, and I joined everything. I joined the WI [Women’s Institute]. Oh, at Derby, I didn’t say, I was a Beaver Scout Leader, I’d been one for about twelve years in Derby and I loved it and when I got here, a lady came up to me, her name was Eileen Buxton, and she said, “We’ve been waiting for you, we want you to be the Beaver Scout Leader”.

So, that was one thing. I joined the WI [Women’s Institute] and I joined a couple of other clubs, but I didn’t like them, so I dropped those off. So, that’s how I was and I got into the village life because I was a Beaver Scout leader. So, I got in with the Church and I’ve never regretted one minute of coming to live here. The only thing is, I can’t get to any of the War Widows meetings because Lincoln is my nearest one or Nottingham. Well, it’s a long way and our bus service is terrible. So, I’ve been to Lincoln, I’ve been to the Christmas one, I’ve been to the pantomime with them. And they sent a car once, the funeral directors at Skegness said they would send one of their cars to take a war widow that couldn’t get to the Forces Day Service. They sent it to me and they said, “Your sister can come. Have you got a sister or your daughter?” And I said my sister would like to come because her husband had been in the Forces. So, we were just like the Queen waving her hands and they took us to Lincoln Cathedral and then he waited for us to come out and brought us home and that was lovely.

I’ve been to three or four conferences. My daughter came with me and a friend came with me to two in the past but my daughter, Carol, my oldest daughter came with me to the one at Wales and it was lovely, we enjoyed it.

So, since you’ve been here, you’ve got a nice support system and friends?

Well, I’ve got friends, yes, but most of my friends, close friends, have died. They lived in this building and we used to have barbecues down on the patio and they used to come up here. We used to have a Race Night and because I’ve got the biggest place, one of them bought those, at home race meetings, and they’re funny, very funny. We used to all bring some food and I’d set it out on the table and then we’d have this race meeting. We used to bet 50p a time and the winner took the money. There was about twelve of us and we used to have some lovely times but four have died and two have moved.

Can I ask you about the rest of your family? You said you came from a really big family.

Oh, yes, there were nine children. Five boys and four girls and I was the middle one. We lived in the middle of the town. My father was in the Forces and he got duodenal ulcers, so, he was invalided out, but they didn’t get anything then.

Are your family around here now?

No, no. Someone said once, big families either keep close or hate each other. I’m afraid we all hated each other. It was a case of fight for everything you had, but we’ve got closer as we’ve got older. I’ve got a brother in Australia. I’ve got a brother in Canada. I’ve been to Canada four times. My sister lives in Derby. My sister-in-law lives in Derby. My youngest brother died of cancer. His family live in Derby. My brother that was in the Paratrooper Regiment, he’s died. His family live in Derby. So, most of my family live in Derby, and it’s such an effort to go to Derby. I have to catch a bus into Skegness, and then the train to Nottingham, and then I get off that and get on another train to Derby. I have travelled in the past. In fact, I’ve been round the world on my own.

Is that since your husband died?

Yes. Since my second husband died. I’d saved the money to have carpet all fitted through here, and had two carpet fitters who said they couldn’t do it because you can’t put carpet on laminated floor. So, I said, “Oh, well you’re turning down a lot of money”. They both turned me down, so I thought, “Oh, I’m going to have a good holiday”. So, I went to see a travel agent and said, “I want to go round the world on my own, flying”. I went on nine flights, and I went all round the world. On the way, I stopped off in Australia to see my step-daughter’s family, stopped there for three weeks. They live in Australia and I stayed there for three weeks. They live in Adelaide, and then on the way home I called at Canada to see my brother for two weeks. I had an absolutely fantastic time.

I spent every halfpenny, but it was lovely. I stayed at really lovely hotels. I’ll tell you about one, shall I? I think, yes, it was Hong Kong. I arrived and the manager met me at the door, so I must have paid a lot for my room. The boys took my luggage up, and the manager took me up to my room. Well, it was like a suite, and it had a granny bed, a grandma bed, a great big one with drapes on. You had to go up steps to climb in it. He showed me how to work the TV and everything, and then he said, “And now”. There was a great big wall like that, and he opened these curtains and it was all glass, and I was overlooking the bay of Hong Kong, and I could see the cruise ships coming underneath. I thought, “Oh, this is nice”. And he asked would I like breakfast in my room or would I like it in the dining room? And I said, “Oh, I’ll have it in my room”.

So, I sat in my nightie at the table overlooking the bay, watching the cruise ships go past and waved to them. There was me in my nightie; mind you, it was a posh nightie. But it was lovely, oh, it was lovely. I held a koala bear. I’m terrified of heights, but in each place I went, I had booked trips to see as much as I could. In Australia, when I first got there, I went to the Blue Mountains, and you have to go in three cable cars. As I say, I’m terrified of heights. The first one went straight across, and I stood in the middle hanging on to the bar, and I looked down and it was glass, and you couldn’t see the bottom. Then the second one went vertical, on a slant down to the bottom, so I went on that. But to come back up, it was dead straight, and it was in a carriage like on a big dipper, that’s all it was, with a bar across you, and you went straight up and it was a long way. Anyway, I did that.

Oh, I did all sorts. When we’d been on this trip to the Blue Mountains, we went in a mini-bus but it’s on massive wheels, so you’re high up and we’d gone all round in this one and we stopped at the edge of a park and then it was like open scrubland and we got out. There was only about twelve of us in this, that’s all it held, and as we stood there, there were kangaroos coming out to look at us, and they were wild ones. Then he got this little table out, put it down, and then he got bottles of champagne out, and we drank champagne at the Blue Mountains looking at all the kangaroos. Oh, it was lovely.

I rode on the tram cars in San Francisco like Judy Garland did in Meet Me in St Louis, up and down on the outside. I sat on the outside. I flew from Sydney to San Francisco, and when I arrived in San Francisco, I hadn’t left in Sydney, which I still can’t understand.

Timelines.

When I got there, they’d lost my luggage, so, they took me to the hotel, and I had a car to take me all the time. I got to the hotel, and the boys ran out for my luggage, and I said, “I haven’t got any. They’ve lost it”. Anyway, they went back, told the manager, and he said, “Don’t worry, we’ll look after you”. And he took me to the desk and checked me in, and he said, “We’ve got everything you need, so you needn’t worry about anything”. Anyway, I got my hand luggage and I always carry a change of clothes in my hand luggage. When they told me at the airport that they’d lost my luggage. Well, they said, “It’s not on the plane. So, here’s $200. Go and buy some more clothes”. So, I was fine with that.

So, anyway, I said to the commissaire in the hotel, “Where’s the best place for me to get some clothes because I’ve only got what I’m standing up in?” And he said, “Hold on a minute”. And he disappeared, and he came back and he’d got two vouchers. He said one was for Macey’s and one was for the other big posh shop, I can never remember that name, and he said, “Go there, and even if it’s in the sale, you’ll still get a 20% off”. So, anyway, off I go to Macey’s, and I bought top clothes and some more underwear, and I was telling the girls, and all the girls came round me in the shop, and she said, “I’ll give you a free gift then”. And she gave me a beautiful Macey’s bag, all wrapped up. So, I brought that back and gave it my daughter for a present. [Laughter]

Do you mind if I take you back to after your first husband died?

Yes.

And then you said that you re-married again afterwards. Do you want to tell us a little bit about that?

When I came here … let me think how it started. I lived in a little bungalow at the top of the village and, of course, as I’ve said, I was a Beaver Scout Leader. One day, my sister-in-law (it’s a bit roundabout – that’s to show you how I knew) who lives in Wales, she said, “Our Bill should go and visit his cousin who lives in Chapel”. So, she told us where they lived and Bill went to see them. The woman was his cousin and her name was Vera, and she was married to John. Anyway, then afterwards, Bill said to me, “Will you come with me to see her again?” So, we went again, and John had only just moved in the house, the bungalow, and John said to me, “If you need anything, I’ll come and do it for you because I can do anything”. So, I asked him to come and put my washing machine in, which he did, and he did lots of things to help me settle in.

Well, John had lived in South Africa for lots of years. He was an engineer and he helped build the roads to the diamond and gold mines. Vera was with him, she went with him there. I think she must have caught something, and when they came back to England she was ill. One day he rang me and he said, “I’m going to see Vera, will you come with me?” He said she’s pretty ill and she was in hospital and I said, “Oh, I can’t, John. I’ve got a meeting that I’ve got to go to. I’ll come with you tomorrow”. So, in the evening, I rang him and I said, “I’ll come with you tomorrow”. He said, “Oh, she’s died”.

Well, then, he knew my youngest daughter. Dawn and I often used to do the things for dos because we had catering in our blood because of my son-in-law, and he said, “Do you know where we could have the funeral, the meal?” And I said, “Well, if you like, Dawn and I will do it for you, make you a buffet at home”. Which we did and then, after the funeral, he took us for a meal. And then one day he rang me and said, “Would you like to come for a ride in my car?” You know, a ride out in the country. And that was how it started.

The thing was, I told you about Bill having no feelings … John was the opposite and he treated me like I was a beautiful princess. It was so different. Because, going back to my family, as a child I never had any love at all. I can’t ever remember my mother or father even putting their arm around my shoulder. So, of course, when John came along, who was full of love … I fell hook, line, and sinker, but he was the same. He said, he’d had an unhappy marriage, similar. Mine wasn’t unhappy, but it wasn’t romantic. No romance in my life. But I did love Bill in a different way. There’s different ways. But that’s how I got in with John, and I had ten years with John. He’s the one that took me to Australia first, took me to meet his family, and we stopped off at Singapore.

And now, what do you do now? Do you get out and about? I know it’s difficult.

Well, I haven’t been out properly for quite a few weeks. It’s seven weeks since I had my operation, and I didn’t know I’d got cancer. The doctor was ignoring me, kept saying to leave things another month and that. I got an appointment with a Nursing Practitioner, and she sent me on a fast-track, and it really was fast, and within days they sent me for a special examination. It was with cameras. Then, on the same day, I had swabs and all those done, and they hinted then it might be cancer and said to bring my daughters with me when I come. They were with me that day, and Carol wouldn’t accept it. She kept saying, “No it’s not, mum. They haven’t said it is”. And I said, “They have”.

Anyway, when we went the next time, we had to go back and see the consultant. He never said, “Can I?” He said, “I’m going to operate”. And he said, “It is cancer. A cancerous tumour”. And he said, “If when you come round you’ve got a stoma on your right side, that means I can put it back. That’s the small intestine … bowel … and we can join that. But if you’ve got one on your left side, I’m afraid we can’t put that back”. But because he knew he couldn’t put it back, he could take … and he told me this, he explained everything, and he said, “I’ve taken a lot from either side of the tumour”. So, when the results came back … I’ve got no cancer now, but I have got to have the stoma bag for always. But that happened very quick. I never dreamed it would happen to me.

But you’re well again, now? Getting well again at the moment?

Oh, yes. When I came ‘round after my operation, I was feeling great and everybody made me feel great. I had dozens and dozens of get well cards and flowers. It was like a florist in here. And everybody was ringing me up. When they saw me, they said, “You look fabulous! You don’t look like we expected you to!” I don’t know what they expected, but I do jump back very quick and that’s why it’s knocked me for six this has [the current illness]. The nurse told me the other day that it was touch and go over this; it was only just in time … . It was neglect because of the doctor, my doctor.

They said on my discharge notes that they were passing my care into their care, and nobody came to me. I had got a bit of an infection when I came out, but it just got worse and worse, and by the time I rang the doctors they said, “We have nothing to do with the district nurses”. They gave me another number and I rang and by then I was nearly screaming at her, and I’m afraid I was a bit naughty and said some things. In the beginning she said they hadn’t got room to push me in, and then I said all these naughty things and she said, “We’ll come and get somebody tomorrow”.

It was four o’clock the next afternoon before they came and the nurse walked in, she put her bag down there, her coat on there, took one look at me, lifted the … I’d only got a gauze on me because I said to the nurse, “I’ve got no dressing”. And she said, this woman that I spoke to on the phone, she said, “Put a towel over it”. And she said, she walked across, she lifted it up, she said, “I won’t be a minute, I’m going to my car”. And she said to my daughter, “Pack a bag, she’s off to hospital”. And that was it, and she asked for a blue-light ambulance which means ‘very urgent’, and it was four hours before the ambulance came. My daughter had to ring and they said, “Oh, we’re sorry”. It was twenty past four when she rang the ambulance, and it was nine o’clock when they were checking me into the hospital. Nine o’clock at night.

That was very good. I think we’re going to look at these –

[NM] I wonder whether you could give us just a bit of an idea about the timelines? So the year, maybe, when you met your husband, and the year that you were married, and the year that he died. Would you be able to explain that to us?

Well, I met him when I was about eighteen, and we married when I was twenty.

[NM] What years were those?

That was 1952 we married, and Bill died in 1992, dead on the forty years to the day. I came to live here in 1993, and I met my second husband about five years after that, and we married a year after I met him. Then we were married ten years … I say ten years, but it was just under ten years when he died.

[NM] Thank you.

And I’ve got two daughters. Carol is 64. She was born in 1953. And Dawn was 60 last week. That’s my baby. 60.

Have you got grandchildren?

I’ve got two grandchildren. As you came in, there’s the pictures of them both graduated. They both did well. My granddaughter is a school teacher. She was a Deputy Head at Immingham, but she’s just moved to a higher position at a school in Skegness. My grandson, he’s … I don’t know, he hasn’t got a title, but he works for Blue Anchor, the big people who own all the caravans and the sites round here. And I’ve got one great-grandson, Marley, and he’ll be six next month, going on 60. And that’s all the grandchildren I shall have. My youngest daughter she’s disabled. She’s got lots of illnesses … had them all her life. So she can’t work or anything, and my life was really wrapped around looking after her, and one thing and another with her.

[NM] Have you got energy for one more question –

Yes.

[NM] – before we move on to the mementos you’ve got from before your husband passed away? You already mentioned that there were some issues that you had with your friends who weren’t particularly welcoming. I wondered what kind of support, if any –

None.

[NM] – you had from government?

None.

[NM] Council?

None.

[NM] War Widows’ Pension?

Oh, well, I’ll tell you about that. They said I couldn’t have a War Widows’ Pension because on his death certificate it said he’d had a heart attack. But he’d been going to hospital all those years with his problems, and he had more [problems] than just his legs. He had all sorts come out on his body, like great big blisters, all on his body, and he was going to the hospital a lot. I asked for his pension and they said no because it said on his death certificate “heart attack”. I asked the [Royal] British Legion and they wouldn’t do anything, and they never did do anything. I was so bitter because he’d given his life, and I always said that the British Legion came first in his life. Carol and Dawn came second, and I came third, and he’d do anything for anybody to do with the British Legion, but when it came to me … I got nothing, no help, nothing.

So, anyway, I can’t remember how long, but they offered me £60 to live on. That was my pension, my ordinary pension. £60. A young girl of eighteen came to the house and I’ll never forget her and she said, “Oh, that’s enough for you to live on”. And I was broken-hearted. I can’t remember how I got going but I did. I got in touch with … and I must have got in touch with somebody because I was the President and then the Vice-President of the Women’s Section of the Royal British Legion. I sold poppies for about 25 years. I’ve got a special brooch they presented me with. I think it must have been through the Women’s Section, I must have got in touch with somebody, and they sent me a form to fill in, and I sent it off to the War Widows’ Association, and they turned me down. Then I tried again. They said I could appeal, and I did.

So, I had to go to London then and I had to go before this committee and there were about five different people in this committee. There was a consultant, a British Legion person, there was a lady, and I can’t remember who else, and there was a secretary who was writing it all down. They said somebody could go with me, and my sister … Sorry, I’ll have to have a drink of water … Her husband worked on the railway so she got a free railway ticket, and she said, “I’ll come with you”. So we went, and the day we went, there was a strike on the Underground and we couldn’t get a taxi, so we walked from the station all the way to … I think it was Whitechapel, I’m not sure. We walked all the way and we asked a policeman and he said, “Oh, it’s straight up this road, ten minutes”.

Anyway, we walked all the way and when we got there, we went and found it, and then we went and found a café that was near, to have a drink and something to eat. So then I went in and I’d got a file, a deep file of my husband’s that they’d sent me a copy of, that came from the hospital and everywhere. On one, and they pointed out one of these, it said that this doctor said that there was nothing really wrong with my husband, [that] his wife was overbearing. Anyway, they said, “What have you got to say about that?”. So, I said, “My husband was very ill all the time and he wouldn’t let me get the doctor and I had to push him”. And I said, “And that particular doctor was a very young doctor, and he upset me. He said that my husband couldn’t speak for himself. I had to speak for him because he wouldn’t, and he would never complain about anything. And my doctor would tell you that”.

I used to have to nearly fall out with him [my husband] to get the doctor to see him and I said, “That’s how he was with the hospital”. And I went in this particular day and told this doctor about these horrible blisters that came out all over his body, and I said [to the committee], “I told him [the doctor] because my husband wouldn’t say anything and that’s why that doctor wrote that”. Anyway, I can’t remember, but it seemed a long time I was in [with the committee], and we came out and this secretary said, while we were out and they discussed it, she said, “Can I look at your rail ticket and your taxi for coming up here?” And I said, “We’ve walked”. And she said, “You’ve what? You’ve walked?” I said, “There was nothing. We couldn’t get a taxi and the Underground was on strike”. So she said, “You have a taxi going back. We’ll pay for your lunch”. And she said, “What about your sister?” And my sister said, “Oh, no, I’ve got a free ticket, so I don’t need any money”. So, she [the secretary] said, “Are you sure?” So, she [my sister] said, “Yes”.

Because we were honest, I think that helped us a bit, but she [my sister] wouldn’t let her [the secretary] give us the money because she’d got a free rail ticket. Anyway, then they called me in and this consultant, all the way through, he’d looked so severe at me and I said to my sister, “I won’t get it because he looked as if he didn’t believe me”. And he said … Sorry, I’m going to cry now … He said, “My dear lady,” he said, “I believe every word you’ve said. And if anybody wants that pension, you do, and you’ll get all your back money”. And they also gave me some money towards Bill’s funeral. So, that’s how I got my War [Widows’] Pension, but I had to fight for it.

Only because you yourself fought for it …

Yes, I fought for it, and of course nobody told me I could do that. Our lady at the British Legion, the Women’s Section, it must have been, either the President or one of them, that said, “You know, why don’t you fight?” Because you sit and tell people your problems, don’t you, when you go to meetings. Not in front of everybody, but when you’re having a committee meeting, you say, “Oh, yes, I can’t get a pension and they won’t let me have it”. I mean, I got full pension for him, and when he got it, he got full pension. You see, nobody gave us any advice when he came out the Army. Nobody at all … never told him that he could get a pension. He said, “If I take it, I won’t be able to get work anywhere”. And it should have been the other way around.

So, they’re very lucky nowadays, and I’m very glad that they have counsellors. Bill nor I never saw any counsellors. Nothing. There was nothing. So, that’s a big step forward, and I think the War Widows [Association] have done a lot towards that, haven’t they? They’ve done an awful lot.

So there’s more support now?

Yes, but I’ve never asked them for anything, you know. When my daughter was ill, and she was ill at one time, you know, I was paying for all the prescriptions, and I didn’t know, we didn’t know ‘til about five years after that she’d already been written as disabled and we shouldn’t have been paying. And I’d been paying all those years for her prescriptions, and it was only once when the nurse came to see her … Because she used to go in hospital and have an operation, and the consultant he used to say to me, “Will you have her at home? You can look after her better than we can”. And he used to bring her home, and I used to have to do all her dressings and everything, and the nurse used to come every few days to check everything was alright.

One day she was writing this big list of dressings and I said to her, “Can you not make it so long?” And she said, “Why?” And I said, “I have to pay for them”. Oh, and she went berserk and she said, “No more. Leave it with me”. She came in the next day with a carrier bag full of stuff. She said … I don’t know whether I should be putting this in writing … She said, “All the old people in Derby were getting every month a box of dressings”. And she said, “The wardrobes are full of them, never been opened”. So she said, “I’ve been round them all, and I’ve got some for you”. So, if you think that shouldn’t be in [the interview recording], you’d better take it out. [Laughter.]

But that’s how it was. I never had anything from anybody, at any time. Neither the British Legion nor anybody, and Bill wouldn’t ask. He was on the committee that gets money for people, and he got it for everybody, but he wouldn’t get anything for us. He said, “No”. He wouldn’t ask for anything.

How long after your husband died was it that you got that pension?

I can’t remember. I think it was about a year, if not more, but I got all my back money for that which was more than he did when he got his. I still think that was wrong that he didn’t get his back money, and I think if we’d have had somebody to fight for him, I think he would have got it. So, no-one, but there was the British Legion and I’m all for them getting all this help they get because my husband should have got some help from somewhere when he was ill because I looked after him all the time and sometimes he couldn’t even get off the settee, and he was very stubborn. He used to go upstairs on his bottom, when he couldn’t walk because we lived in a house and he used to go upstairs on his bottom to go to bed.

And all his injuries and illness were due to being in action?

Yes, being wounded, and I think my daughter’s illnesses are to do with it because they keep saying they don’t know what’s caused it. It’s not hereditary, and she’s had that many operations and that many things wrong and I’ve always said … He laid in the jungle in Korea – and I only know what he told me – for two days before he was picked up, and it was monsoon time. So, he laid in the jungle for two days and two nights before they found him, and do you know who he said found him? Salvation Army people, they were right up behind them on the frontline.

And that’s how he got rescued?

And that’s how they found him, and they got the helicopter and he was one of them that came out on a stretcher and was taken to the MASH station. We used to have to watch all the old MASH things, and he said, “That’s exactly how it was”. Just as it showed you on the film, them running out and then coming back and operating and getting down on the floor when they hadn’t got an operating table. And he said it was just like that. But he wouldn’t tell us anything about it, and I know lots of things happened in Korea because I could hear them talking, but they wouldn’t let me hear them. They said that it wasn’t for women to hear, and it was those [veterans] talking between themselves, and it must have been a horrific time. I understand now, more than I did then. When you’re young, I used to think that he’s got no feelings, and it must have been true, he must have left them in Korea. I was so sorry when he couldn’t go to Korea to be presented with these things.

[NM] Shall we take a look at them?

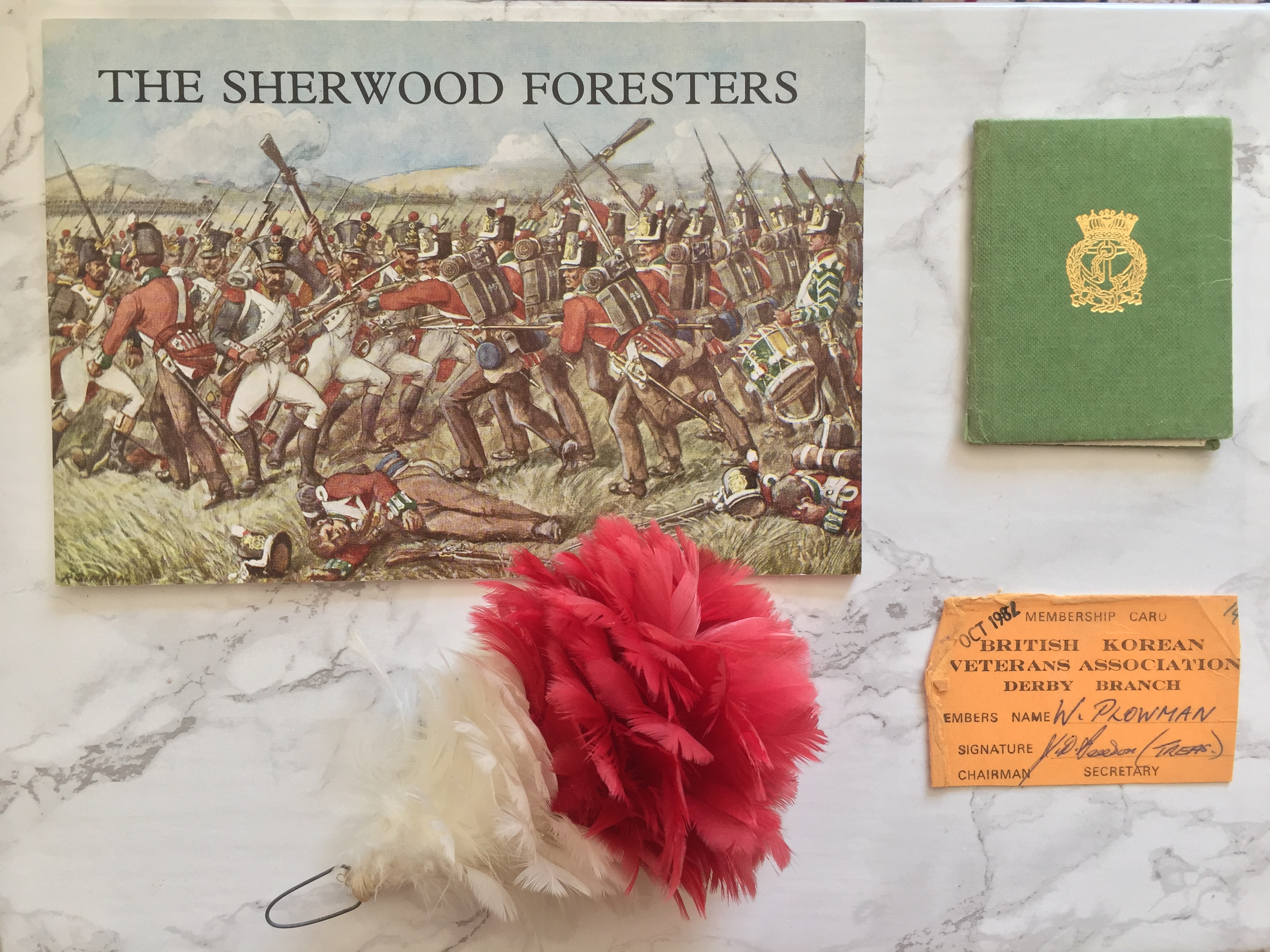

Yes. That’s his Northumberland Fusilier thing, but he was in the Sherwood Foresters. That was his little sailor that they gave him on his 21st, and that’s the ship, the HMS Fowey, but it was a cruise ship.

So, can you describe it again for us, Sylvia? So, he was given this …

He was given that for his 21st birthday on the cruise ship. They were on beds on the deck, the two of them, and he said they were spoiled silly by all the people that were on the cruise.

This was after he got out of Korea, wasn’t it?

Yes, this was when he was coming back from the hospital as a wounded soldier, you see, coming back to England. They were his medals.

Right, what have we got here? There’s two.

That’s his Korea one.

So, this is from Korea?

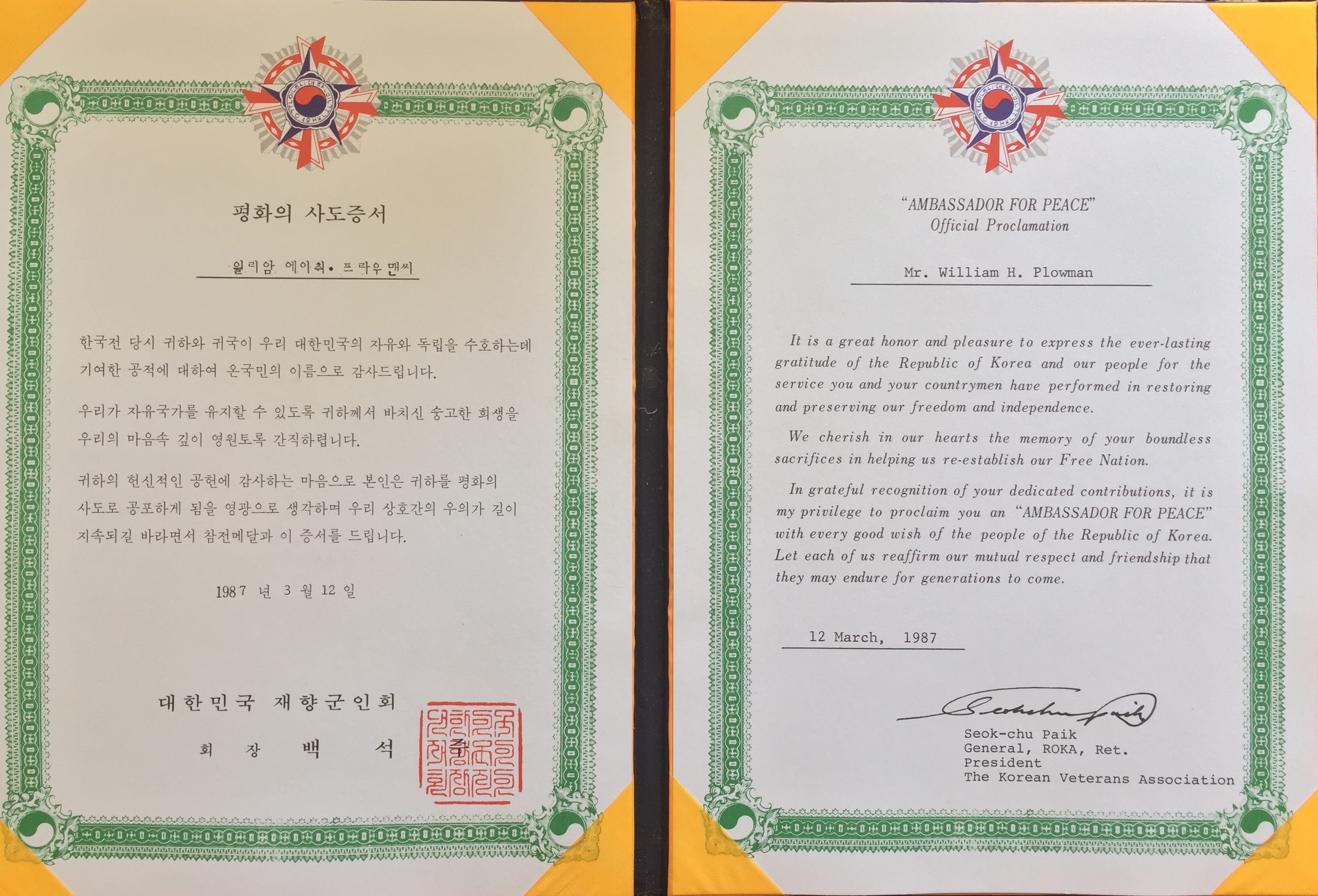

Yes, the South Korean government. Yes, it’s just the two. One’s in Korean and one’s in English.

That’s lovely.

And this goes with that. These are what they sent him and they go with that. On Remembrance Sunday, I wear the little one.

Where do you go for Remembrance Sunday, Sylvia?

Here, at our Church in the village. I always have a wreath, I always ask for my wreath and they send it me.

Have you ever been down to London for Remembrance.

Once.

Did you? With the War Widows’ [Association]?

Yes, once, but it’s quite a few years ago. Oh, I did the walk across, and I’ve got that in there. Yes, I did the walk across at the show [on Remembrance Sunday].

The British Legion one, yes? What year was that? Can you remember?

No. Quite a few years. Anyway, I’ve got it in that cupboard there, the programme and that’ll be the year. It was the year that singer wore the poppy dress.

That’s twelve years ago. Can’t believe it’s twelve years. I didn’t tell anybody I was going, you know, and they were all saying the following week, they were saying, “Was that you on the TV?” And I said, “Yes”. Well, I didn’t want them to think I was bragging.

They’re all my Courages [the War Widows’ Association newsletters].

[NM] Oh, you collect them all?

They’re all in there, yes.

So, is that your contact run out with the War Widows’ [Association], you don’t see anybody else?

No, nobody comes to see me. I put an advert in the paper, local paper, to see if there was any in Skegness who would like to come and join me for a cup of tea or coffee and nobody answered. Nothing.

I would like to go to the Forces Day again. I’ve been to one at Nottingham but it took me that long to get there.

Oh, it’s in Liverpool this year.

Yes.

They had one at Cleethorpes one year, didn’t they?

Yes, and I was going, but something happened to stop me because there was one of the coach services was running a coach. Oh, I know, he was going at nine in the morning and he wasn’t coming back ‘til nine o’clock at night and it was too long and I couldn’t get back from Cleethorpes on my own. I think my daughter was away on holiday because she’s got a car, but she works full-time, you see, so it’s just now and again.

This interview transcript, its print and online versions, and the corresponding audio files are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives Licence. This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as the work in question is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to War Widows’ Stories. If you wish to use this work in ways not covered under this licence, you must request permission. To do so, and for any other questions about this interview, how you may use it, or about the project, please contact Dr Nadine Muller via email (info@warwidowsstories.org.uk), or by post at the following addressing: John Foster Building, Liverpool John Moores University, 80-98 Mount Pleasant, Liverpool, L3 5UZ.