Denise Haddon’s father, Ronald King, was killed in Malaya in 1942, when Denise was an infant. She tells the story of her parents’ relationship and describes life for her mother, Elizabeth Cooper, as a widow. Denise details the hectic early years of the war which her mother spent in Ireland before returning to Hounslow in 1947 where Denise was raised by her mother, grandmother and aunt. Denise talks about travelling to Singapore to visit her father’s grave in Kranji Cemetary, and about the implications of losing her father as a baby. Conducted by Clare Baybutt on 5 April 2017 in the company of Ailbhe McDaid.

Click here to download the transcript of this interview as a pdf file.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

[AM] It is the 5th of April 2017 conducting an interview for the War Widows’ Stories project with Denise Haddon, maiden name King, in the company of interviewer Clare Baybutt and project representative Ailbhe McDaid. For the record can you state your name and your place of birth please?

M y name is Denise Haddon, and I was born in Dublin, Republic of Ireland.

y name is Denise Haddon, and I was born in Dublin, Republic of Ireland.

Ok. Well, we’ll start with a bit about yourself currently, your current life?

Ok. Well, at the moment I see myself, apart from the nice visits to concerts and theatre, such things, I see myself mainly as granny to six grandchildren, and I do a lot with and for them, but [I am] also chief carer to a 100-year-old aunty, not that she’s living here, but she’s living in a care home nearby. I do everything financially, organise everything for her, go see her every day. That’s it really.

Following on from that question: past profession … What did you do?

In the early days I worked for the Foreign Office, and then for the BBC, and then for the Jesuits in various capacities, mainly secretarial / PA type work, although for the Jesuits there was some financial management in their Fundraising department. Subsequently, after having children, I retrained as a teacher for teaching refugees and others. ESOL, English for Speakers of Other Languages, it was called at that time. It’s changed a bit now, but that’s mainly what it was, and I did that for probably ten or twelve years before I retired.

Moving onto your childhood and early life … Hometown?

A mixture. I was born in Ireland because my father went off to war, my mother and grandmother, who was herself a widow, were moving around quite a lot between England and Ireland, and it was a weird time because you couldn’t just travel willy-nilly. You had to have somebody to claim you in each country, so my gran always had to go first because she had children here, and Mum could then follow with me, and then to get back to Ireland her brother over there could claim, so it was it was all very strange. So that was to-ing and fro-ing. There was no actual hometown. It was Enniskerry, County Wicklow, for a long time; Bray, County Wicklow, for a long time; and then to my grandfather’s in Brookmans Park in Hertfordshire for another long time; and then Woking in Surrey, where I started my first convent school. And then, in 1947, they all moved back to the original house where my mother grew up in Hounslow in West London. So, from the age of about eight onwards until I was seventeen, that was where I was living. It was Hounslow and Cranford, so it was kind of on the edge of Hounslow. Planes didn’t quite land in our backgarden, but nearly.

So the reason for that moving around, was that military?

No, it was just not quite knowing what was happening, maybe one lease coming to an end or the desire to see family who worked for a living over here. But it was mostly Ireland until I was three, and I think it was at that point around about then that Mummy heard that my dad had been killed. I think I was three or four. I’ve got some letters, actually, that I can show you where they were. They give the date of when she … I think I was either three or four when she finally heard that he had been killed. Up to that point she didn’t know, although she always said she felt it in her bones that he wouldn’t be coming back.

How did that affect your early life?

I think it probably did, you know, if you think that babies pick up emotions and things from their mother. There must have been stuff there that was coming across. She used to talk about my father a lot. Lots of stories about what happened when, and even those early days when he was in Enniskerry and Bray, before he went off, she used to talk about that a lot. Quite a few amusing stories of him pushing the pram in Ireland in 1941. I think he probably was the only man in the whole of Ireland who would dare to push a pram because everyone else would think it was woman’s work, “You mustn’t push a pram”. And he actually changed nappies, which absolutely scandalised the woman of the house. “A man changing a nappy!” So, there are a lot of quite amusing stories. But yes, of course it does affect you, and it leaves a big gap in your life not to have your father.

With the moving around, is that something that affected you in making friendships easily?

I don’t think I thought about it. You know, in babyhood it’s neither here nor there once you’re with your mum and the people who love you, and as a small child playing in Enniskerry, there were no cars. Nobody had a car. Very few people had cars. We’re talking about the early forties – only rich people had cars then. So, the door would be opened in the morning, and I would go off. My gran used to go off to Mass every day, and I would sometimes run off to meet her, and you could let a little thing go off like that. Everybody knew everybody else. Everybody knew if there were any strangers around. Everybody looked after everybody else’s children, gave them a clip round the ear if they needed it, a cuddle if they needed it. It was a different world. So, my memories of being there are very fond.

What was your education?

Convent schools. Started off at a convent school in Woking. I was a day girl for one year, and then I was sent as a weekly boarder when I was six, which wasn’t a happy experience. And then after that, when they moved back into their Hounslow house, I was then sent to a convent school in Ealing, and I was there from age seven to seventeen, and then I went off to France for a year, to a convent school in Paris for a year. So that was nice.

You mentioned [as] a weekly boarder you were unhappy …

Yes, it was hideous. It was awful. I hated it. I was very scared. I missed being at home, but I was by no means the youngest child there. The youngest was about three, I think, and she used to rock herself to sleep every night. There was no unpleasant behaviour on the part of any of the nuns that were teachers or anything. It wasn’t that I was cruelly treated. I wasn’t. It was just that I was unhappy at being away.

What was your mother doing during that time?

Do you know, I don’t really know. They had to go to court to get their house back. It was the 1940s and the government at the time were very much of the opinion that, I don’t know, they didn’t want to put out people who were renting. They didn’t see why landlords should claim the house back. And they had to go to court. The lawyer of the person who didn’t want to move out was very unpleasant and scathing and accused them of running away from the bombs, “Only too happy for Mrs whatever-her-name-was to have the house while you were running away from the war”, which was a very cruel thing to say because, in fact, she had left before the war started and was nursing a dying daughter. So, it wasn’t very pleasant. But the judge, in the end, found in their favour and they got the house back and that’s when we all started living [together], and Aunt Lena, who’s now one hundred, came to join us in the old family home, and it was those three women who brought me up really.

And how was that, being brought up by three women?

Well, I didn’t know any different. I had male cousins and I used to love it when they came over. It was a funny time, though, the war was all around you. When television first started coming in a lot of the television programmes were all about soldiers, and the war, and the “Laffe” [Luftwaffe], and Vera Lynn, and the wartime songs, and it was all still going on. It was 1947 we moved there, so I’d have been six. So the war was very … Yes, it was part of life still. I remember once walking along with Mummy, and it was the first time I was aware of Remembrance Sunday, and we were just walking along the road and she said, |We’ve now just got to stay still for a minute because it’s eleven o’clock, and we just have to say a prayer for Daddy and all the other men that died, and this happens every year”. I think I was about five or six when that happened, and I always sort of think of her on Remembrance Day. But having said that, she was always very aggravated by all the fuss and parading up Whitehall because she felt the war widows got an absolute bad deal. She used to say, “German war widows are treated as heroes’ wives, whereas some of us actually couldn’t afford to live”. She managed, but she got letters occasionally from the tax people, asking if her father-in-law had given her any extra money, and she was absolutely livid. “Even if he had, so what? I gave you my husband!” So, she was quite cross about the way widows were treated.

Did she ever explain further? What was her opinion?

What, why she felt that?

What was her experience of it?

Well, I think probably because she was widowed when she was 28, my father died just before his 30th birthday, and I think she felt cheated, really. Part of me thinks, well it’s his fault because he shouldn’t have gone off because, actually, he had a job that was protected. He was in the bank. He could have stayed at home, but he felt it was his duty to go, and so when he thought that there was going to be a war, he joined the Territorial Army, and of course when the war broke out then he was called up. But he did have a very promising career, and so I know that, apart from losing him, she also lost a different lifestyle from the one that she had. Obviously, she wanted a big family and she wanted to not have to watch her pennies. Now she realised that she was lucky to have a few pennies to have to watch and be able to spend, and she didn’t have to go out to earn a living because she could just manage on the pension that she got from the war and from my father’s work, I think. I think that’s how she managed. But there was never a lot of money around. Not that I felt deprived, I didn’t. The army paid for my education because in those days officers’ children had to be privately educated. You couldn’t go to an ordinary school.

How do you think other women saw military wives or military widows?

I don’t know. I don’t know. I can’t comment on that. What do you mean, from the point of view that they were getting a pension?

What were the views of people who were married to men in the military, because they got benefits, did you feel there was a different attitude to people?

Not really. It might have been different if my father had been a career soldier, I don’t know. I don’t think it would have done. My father-in-law actually was a career soldier. I don’t know, I can’t comment on that really. I never came across any sort of comment. It was such a funny time. There were so many people who came back so badly maimed or psychologically damaged through it all that you felt lucky to be alive yourself, and my father always said, apparently, before he went, that he’d rather die than come back wounded or maimed, so he got his wish because he would have been paralysed if he’d come back. He got a bullet in the spine.

What was the sense of community? Was there a military community in those times?

No, no. Do you mean that Mummy might have been part of? No, not at all. Not at all. She had absolutely no connection with anybody. It probably would have been different if he had been a career soldier because I know my mother-in-law did an awful lot of work with the wives in her husband’s battalion, but Mummy, as far as I know, never had any contact. The only contact she had was she got a letter from somebody once, and she used to have it, but I don’t know what’s happened to it because I haven’t got it amongst the bits here. But his watch, his wristwatch and his fob watch – you know these big watches men used to have in their pockets, a pocket watch – was sent back, and he said that it was a bit battered because it had been through all sorts. He’d carried it with him throughout the war and was just returning it to Mummy. He gave her one piece of information which she didn’t know: they used to call my father “Rock”, apparently, because his initials were R O C K, so he was known as “Rock”. And that’s the only contact she had with any of them, and he was just a fellow officer who returned those things, otherwise it was just formal communications from the War Office.

And that’s how she was informed about his death?

There must have been a letter first of all saying he was missing, presumed killed in action, and then eventually they got the information in 1945. I think 1945.

Was that in person or by letter?

Yeah, letters.

So there wasn’t any person there to come ‘round?

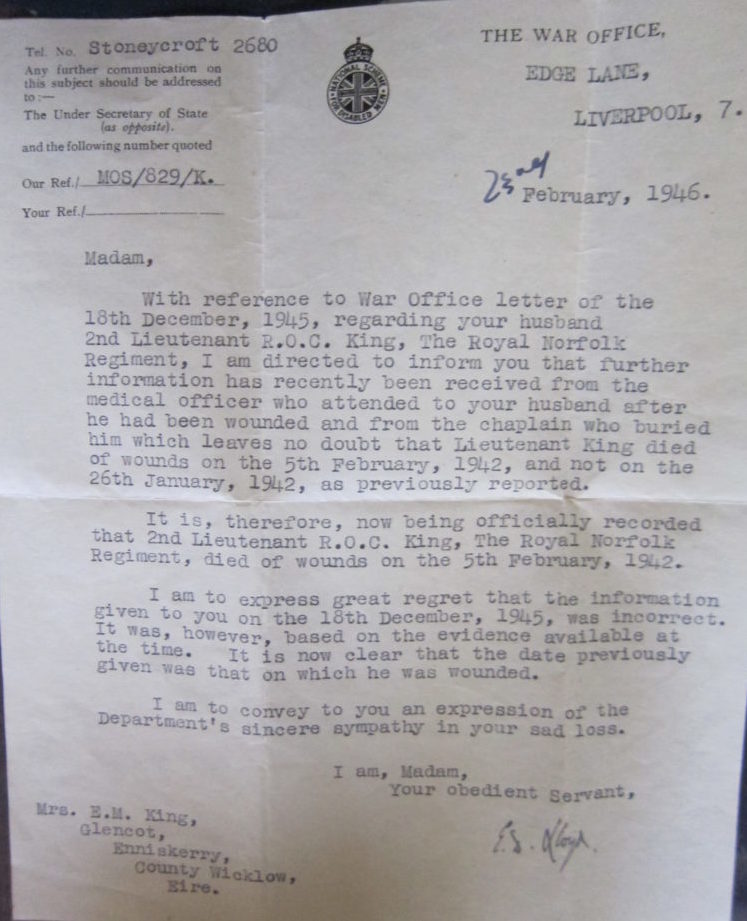

You see, I have a memory of her receiving a telephone call when I was at my grandad’s house, and in my head it was always that this was the call that confirmed it, but I never knew whether it really was. Because she was crying and my mother didn’t cry. So maybe it was, or maybe somebody reminded her of something. So, I mean that it would have been the right sort of time, that would have been in 19… No, I can’t remember. No, it was all very cut and dried. The first info she got they had to correct. It was wrong because they gave her the date that he was wounded, and they thought that was the date of death, but it wasn’t, in fact. It was quite a letter, apologising … They’d had further information from the doctor who had attended him and the padre who had buried him, so she knew he’d been properly buried, and all the rest of it. I can show you those later.

Letter from the War Office confirming the correct circumstances of Ron King’s death. 23 February 1946.

Did she ever talk about that moment when she found out?

No. No. All she’d said was that she’d gradually realised that he wasn’t going to come back and that, for her, that gradual realisation was a far better thing than to suddenly out of the blue to get the telegram, so that when the letter finally came, it just kind of confirmed her own gut feeling. But she always said there was no way she wanted to marry again. She wasn’t looking for anybody else. She always used to say she didn’t really know what married life was like because they just had a honeymoon really. She came home, she was sitting behind two women on the bus, and they were both having a good moan about their husbands: what this one’s one had done, and what the other one’s one had done, and she said she felt like tapping them on the shoulder and saying, “You thank God you’ve got them, however annoying they are”. But she didn’t, she’d probably have gotten a punch on the nose if she had. They were really brassed off! [Laughter.]

Where did they go on their honeymoon?

Well, I don’t think they had a proper honeymoon. Well, they got married in early February 1940. I think it was 1940 they got married. And they didn’t have a “floating down the aisle in a white frock” wedding. It was a suit and very much an austerity wartime wedding at the local Catholic church. I don’t know at what point he got his commission. I have got one interesting thing: one of the letters he had sent because he had started off in the Queen Victoria Rifles, you know, when he was called up they stuck him down in Kent somewhere, and a Christmas card that he wrote to her from there which I scribbled all over when I was a small child. And there is a letter which he sent after he had left them and had got a commission in the Royal Norfolks, and he had heard that his former colleagues had been sent off to … I don’t know if it was D-Day or what it was … but they were sent off to an attacking situation whereas in fact they hadn’t been trained for any of it, and he was very, very angry and just says, “So, 1914, here we go again in 194—(whatever), to the everlasting disgrace of those in charge”, so it’s quite strongly … I keep thinking I should send this to the [Imperial] War Museum. He was very upset by the fact that the people that he had trained with had been wiped out, and he would have been one of them if he hadn’t gotten his commission.

Did your mother know any of his friends in the military?

No. There was none. It wasn’t really the time for socialising.

Do you know much about his training? How long he was training for or what your mother might have thought about that?

Not a lot. I don’t think she was wildly happy he was going off, but she understood that he needed to, that the men had to go to do what they all thought was their duty. All I know was that when he was in Kent, she was at home with her [father] in Hounslow, but then when he was up in Norfolk, when he was sent up there, she got digs up in Kings Lynn. She sort of followed him around a bit until it was clear that he was going to be sent away, and I think by then she was pregnant. I think then she moved down to Hertfordshire to live with his mother, and for some reason he was coming and going there, too. Perhaps he got some sort of extra leave then. It’s a bit patchy. Memory is a bit patchy. I don’t even know if she even said why he was around.

But she then started agitating to go to Ireland because she wanted to be there rather than at Brookman’s Park when he was being sent off, and so there was a big conflab because he didn’t want her to go because Aunty Frankie had TB [Tuberculosis], and he didn’t want her to be at risk and me to be at risk. So in the end she was fretting so much that he said, “Right, well, go and see the doctor what-ever-his-name-is, and if he says it’s alright I’ll give you my blessing”. So she went off on her bike and when she came back, he looked at her and said, “You don’t have to tell me what the doctor said. It’s written all over your face”. So she went off to Ireland while he went back to training, whatever he was training at, and then that was when he came to Ireland. The morning I was born, in fact.

It was Sunday, and there was no transport. Have you ever arrived in Dun Laoghaire? If you look up on the hills, you may not have noticed, but there’s a single chimney pot on one of them, and it’s called Katty Gallagher, and he knew if he could get to Katty Gallagher that he just had to drop down the other side, and he’d get to The Scalp, and then he’d be able to walk into Enniskerry, which is what he did. So he did it all on foot. And when he got to Enniskerry, Gran said, “Ron, she’s in Dublin, the baby has arrived”. Apparently, he arrived at Holles Street Hospital, and the sister came in to Mummy and said, “Mrs King, there’s a fine young man outside claiming to be your husband”, and Mummy said, “Don’t be silly. He’s in England. He is in the army”, and she said, “Well I wouldn’t be sending him away if I were you. He’s gorgeous!” Anyway, he walked in and that was it. She always used to say, “This is the spot”, all through my childhood, every time we were on the bus from Dun Laoghaire or Bray or whatever, she’d say “This is the spot where Daddy crossed the road to get up to Katty Gallagher”. It all looks a bit different now. Whenever I go backl, I say which is the spot. All the houses have gone up and the roads have changed.

Did she ever talk about how they met?

They met because they were colleagues in the bank. They both worked for Westminster Bank, and they were at Kensington, just opposite Kensington Gardens, so that was why they used to stroll around Kensington Gardens. Apparently, in the early days he used to be driving around in a green little MG car. She thought, you know, he’s got ginger hair and is driving this flash car, wasn’t sure, but anyway in the end they hit it off.

Do you know much about their life before you came along?

No. I know he liked teasing her. She was terribly Irish at heart, my mother. She absolutely loved Ireland with a great passion, and she absolutely loved a singer called John McCormack, and she insisted that my father went with her once to the Royal Albert Hall where John McCormack was going to do a concert, and of course the place was packed full of people because he had a big following, and Mummy was sitting there thinking this was marvellous, and then John McCormack started singing a song, and there was a line in it and the words were, “It’s time I was moving. It’s time I passed on”, and, apparently, my father yelled out, “Hear, hear!” in a very loud voice, and my mother nearly died. She was mortified that he’d been so rude to her great hero, and he wasn’t very impressed, but it was probably mainly to tease her rather than show disrespect for the great man. But he did like teasing her, he liked fooling about. Apparently, once he tipped my pram up because he was so busy fooling about and, luckily, I shot down under the apron rather than over the top, but he wasn’t popular. So, she used to enjoy talking about it. She liked talking about it. And she always used to say … You see, I was very like him. I had bright red hair when I was a child, and I did look like him even when I was an infant, and apparently one of her stories was he saw me the morning I was born, and he was there for a couple days, and then he had to go back, and then he came out again on embarkation leave for six weeks, but when he came back, apparently, she looked at him and said “You’ve changed”, and he said “What do you mean I’ve changed?” “No, you’ve changed, something is … You’ve changed”. “Well what do you mean I’ve changed?” “Well your face is changed”, and he said, “What do mean, my face has changed?”, “Well, you … I don’t know … You look coarse!” He said, “Don’t be so silly. You’ve been looking at that little thing whose face is so like mine and because she’s got this little delicate skin and everything you now think my face should have this little delicate skin”. Anyway, that’s another of her stories, that she accused him of being coarse. I was like him, and some of the reactions as I developed were very like him, so she always said I was his child rather than hers. She looked very different to me, she had very dark hair, quite an Irish face, really, grey-blue eyes put in with smutty fingers.

Did she talk about him more later on in her life?

She didn’t believe in outwardly showing grief. She said you can’t go through life crying, whatever happens, you know. You’ve have to make the best of what you’ve got. She was a very cheerful happy woman. But the bottom line was losing the man she loved at a very young age. You can’t imagine it, really, can you? I mean, I grew up, you sort of took it for granted that this was where it was at, but you know I lost my man when he was 71, and I know what that was like, but we’d at least had our family together and all the rest of it, but Mum, you know, all her dreams were chopped at the root almost, but she still had a big spark of life, and she knew that life had to go on. And, of course, once I finally got myself married, which she was so disgusted about … “When are you going to get married? You’re not going to find a man made of chocolate who you can mould exactly to your wishes!” “When the right man comes, I’ll marry!” Anyway, I did, thank god, find somebody whom she loved to bits, and when the grandchildren came along, she was a marvellous, marvellous granny. She didn’t stand any nonsense but she was a marvellous granny. Sewed and made clothes, babysat, played cards, you name it, she did it. So in a way they were her ones she didn’t have. Absolutely devoted to them. And they to her, I have to say.

Her life immediately after she found out … Can you talk about what that entailed? Her benefits, how she was treated after that as a widow?

Well, I know she got a pension from, I suppose, from the War Office or Pensions Office, whoever it was who provided the pensions, and when I started school, they paid my school fees, and I don’t know how all that was organised. And she also had a bit of a pension from the bank. Of course, she was taxed on everything. There was no waiving of tax of any sort, and there was one occasion on which, because she had been moving around and had been in Ireland for a while and then came back to England, whether it was to do with a change of address or something … Anyway, the tax people found, quote unquote, her again and, anyway, suddenly at the end of a particular month she looked at her bank statement and a whole huge amount, I mean most of the money, had been removed to pay a tax bill. I don’t quite know what had happened, but they had made an assumption about her and her finances and just taken the money, which they were apparently entitled to do, and so she was in quite a bad way financially at the time and really had to have a big fight to put things right. She was livid, because she felt she’d not only given them her man but they were now trying to take all her money as well.

And it was after that that they were prying into all her details and wanting to know if her father-in-law had given her any money or if she’d received money from any other source. So, she was cross. I mean, she didn’t have loads of money, but she had enough to live on, especially as she’d clubbed together now with her sister, who was earning, so they were sharing household expenses. It might have been different if they hadn’t done that. I don’t know enough about the nitty gritty of it to be able to give you any proper information because she never believed in talking to children about money.

She didn’t remarry? You don’t remember any other men in her life?

Gentleman callers? No.

You don’t know if she ever took up with anybody?

No, she always said she was a one-guy gal. And, you know, it was a different world then. She was brought up as a good Catholic girl who didn’t have sex before marriage. She believed that people should be chaste if they weren’t married, so you know. Who knows. She certainly didn’t discuss any of that with me, and I certainly wouldn’t have asked her, you know. It’s a private business, really, isn’t it? But she had very strong views on that subject, and they were the traditional Catholic views.

Growing up, was there childhood friends who had fathers? Did you feel like you were missing out?

Oh yes. Yes, hugely. I felt I was missing out on having brothers and sisters. I would have loved to have had brothers and sisters. I felt I was really cheated of that. Yeah, it’s a gap. It is a gap. It’s a big gap in your life if you’ve got a significant part of your family that’s missing. But I do feel very strongly that it is a very, very large gap.

Were you around other children who didn’t have fathers, who were lost in the war?

Not a lot, surprisingly enough. I think there was just one other girl in my class. It’s interesting, isn’t it, because you’d have thought there’d have been more. There was only one other in my class whose father had been killed. It wasn’t anything that was ever discussed, you know. You just took it for granted that that’s the way it was.

How do you think they treated people who came back disabled because of the war? Is it different then to the way it is now?

I don’t know. I think the difference is now that people are more willing to accept that people are damaged by these experiences, by the experience of war, and that the people who are damaged have nothing to be ashamed of by being damaged. It’s more open, I think. The whole society lets much more hang out now. I might argue too much hangs out, but you know. You’re expected to weep at every turn, whereas we weren’t allowed almost to cry. But there’s no doubt about it that then it would be probably a sign of weakness. You’d be a bit of a sissy, especially a man, you know, if a man broke down because his nerves were shot, it would be unthinkable. So, I think from that point of view I think the guys now, if they’re damaged, probably have a better deal than hitherto, but I don’t know. I don’t know anybody in that situation. I just get the feeling from the general way it’s talked about now and, you know, all the stories of people coming back from World War 2, so changed and so damaged that their wives couldn’t live with them anymore, and you’d meet people in the streets sometimes whose faces were totally disfigured because maybe they’d been in the RAF and their planes had caught on fire, and so there was this awful plastic surgery they used to have, and their faces would be completely disfigured. Frightening to look at. Very, very scary. Like something out of a horror film. I suppose plastic surgery was sort of not as sophisticated then as it is now. They can do a better job, but imagine those men. Imagine if your man came back totally damaged. You couldn’t even recognise him, and his personality had totally changed. It would be a hard ask, wouldn’t it, to stay in the marriage. And yet, you know, the poor guy.

What was your sense of masculinity then? Were they more secure because they all went through the same thing or was it more fractured?

I think there probably was a certain amount of solidarity because they all went through it together. The ones who’d have been out on a limb would have been the conscientious objectors. They’d have been thought of as big sissies, cowardly and whatever. The whole atmosphere was that you fought for king and country, and you were doing your duty as a man, and that was what you had to do. There was certainly no talk of women being in the front line then.

Is there any particular instances stand out for that time? When you’re thinking of being a child at that time?

The reason I mention the guy with the face … I was coming home from school, I think it was dusk, and I came around a corner, and this guy was coming in the opposite direction. I knew instantly what had happened and what it was, but it had given me such a fright, and then I realised I was trying not to react. I was very scared, but I did realise what was the matter, and then I felt terrible because I had jumped because I realised that was the way he was because he was fighting for us. It was for us. There was very much a sense that these men did this for us. And that’s gone now, of course.

Who were your male figures growing up?

I suppose my uncle, and I had three boy cousins, the parish priest, the doctor, various married friends of my mum, two or three of those. People in Ireland that I knew and used to see once a year, my old [great-]uncle, who used to shave once a week to go to Mass, and brothers of friends. There were a few chaps around.

None of them in the military or joined the military at all?

No. Not in my childhood, no. But later my cousins did, but that was later in the 50s and 60s. And, really, by that time you are one removed from it all.

So they weren’t influenced at all to join the military because of the family?

No, not at all.

Can you explain the best you can the details of your father’s death and what position he was in?

My understanding is that he was on a ship that was supposed to be going to India, but it was diverted, and I think it’s because Pearl Harbour happened, but I can’t be sure of that because of the dates, but he would have left in late September/ early October 1941, and then he was set sail then. And he was sent to Malaya, and there was a place called Senggarang or something like that? There was the feeling that the Japanese were close, and nobody quite knew if they had landed or not. And, apparently, according this fellow officer of my father’s (I wish I still had the letter – I haven’t), they were doing reccies to see whether there were any Japanese, and he led out a party to see if there were any of the enemy around, and a Japanese sniper got him in the spine. And he was carried back. The men carried him back, and he died of wounds. I thought he had been injured in December 1941, but looking at these letters again this morning, it seemed to say that he died in January. No, he died in February, but he’d have been injured in January. I don’t want to make any noise because I will rustle and make noise on your machine, but you can look at them later, if you like. So that’s all I know, really. He was attended, he was brought back, we knew he’d been shot in the spine. He was attended by the doctor, he was attended by the padre, and he was buried.

Mummy used to say when she died she’d like her ashes to be taken out and put in the grave with him. I thought “What?”. I said, “They probably wouldn’t let you anyway, and I don’t want to do that”, There was an offer at one point where they would take people out to visit their husband’s grave. They would actually pay for their fare? Do you remember there was some scheme? Anyway, she would never do it. She felt it would be too much, emotionally. It would cut her up far too much, and so she never did it. So, I said I would go before I died. So we did.

So you visited, but she never visited while she was alive?

No. Paul and I, when our Patrick was in Japan, we thought, “Right, we’ll do this big Far Eastern trip”, so we went to Singapore first and found my dad’s grave and then to Manilla to stay with an old school friend of mine, and then we went to Japan.

What was the place of burial like? Was it a monument?

It’s a big military cemetery in [Kranji] in Singapore. Fantastic. I did know where I was going. I had the details printed out, of the grave, and the grave number, and the row and whatever. When you go in there, they’ve got this big fancy entrance. In the wall where you go in, almost like a tabernacle or something, a little cubbyhole in the wall and you can open it, and you can get out a book, and they have the list of everybody who is buried there. It’s manicured within an inch. The grass is cut within an inch of its life. It is so beautiful. The lines are straight, and all the graves are beautiful, and each grave has its own flowering shrub. It’s beautiful. So, I found his grave. Quite a lot of graves with “Soldier known only to God”. Just so sad they had the body, but no name. Then they had loads, right at the back, almost like a big pergola, I don’t know how many walls, with a roof over the top, but open at each side, and each side of the wall names of all the people who had been lost. They had no bodies. They just had names. Incredible. Loads of Indians, Singhs, loads and loads, Commonwealth names, quite horrifying, but wonderful to see it all commemorated. They’ve done a beautiful job out there. I mean, I haven’t been to any of the war graves in France, so I haven’t seen what they’re like, but this was quite spectacular, really. Quite moving.

Ron King’s first grave at Changi cemetary. His body was later reinterred at Kranji Military Cemetary in Singapore in 1946.

How did that make you feel?

A bit choked up. I had a little bit of a weep.

Your husband, did he have any knowledge of the military? What was his reaction?

Well, I mean he came to support me. He came from an army family. His father was career army. He was Commanding Officer of a battalion that went in at Arnhem, and he was a prisoner of war after that. He was captured at Arnhem. So he was a career soldier. So Paul was brought up in a military family, really, but he’d been at boarding school here all his life because, in the early days particularly, they didn’t pay for kids to fly halfway around the world. So his mother was a CO’s wife.

So did your mother meet his parents?

Oh yes.

How was that relationship as a military family?

It was fine. Nobody thought that much about it, really. I mean it would have been different if Daddy had been [a] career [soldier], but it’s a different kettle of fish really, isn’t it. But they got on perfectly well.

So, other extended family members … What was their experience of your mother’s loss?

Well, I suppose the people who were most affected by it were of course her own mother, and her sister, my aunty, Aunty Lena, because they were the ones who sort of were with … Well, Lena wasn’t with her, but Gran was with her, but they were the ones who decided to make a life together after they got the house back in Hounslow. But it was particularly my gran because she and Mum travelled around with me. It wasn’t until they got that house back that the three of them got together again. Apparently, I was quite sniffy about Aunty Lena at the beginning. “Who is this woman coming in who I don’t really know very well?” So they’d had a fearful time because in February ’41 – that was when Mummy was expecting me, and Daddy was in Norfolk, I don’t know where Mummy was, probably in Norfolk as well – their father, Mummy’s father, was killed in a car crash, but my gran was nursing daughter number two in Ireland at the time, so couldn’t get back for the funeral. So that was their first death, and then I was born in the August, and then Aunty Frankie died in the October, and my father died following February, so it was a bit of a difficult, quote unquote, time. There was a lot of grief around, but they all supported each other. What can you do? You’ve got to get on. My gran used to say to me, “Darling, you were the one who kept me alive” because of course my nappy needed changing whether they were sad or not.

How was it explained to you as a child about grief or death?

Just that Daddy had died in the war. I do remember once being in the garden with Mummy, and saying, “Oh it’s really not fair. God took my daddy away, and I couldn’t have any brothers and sisters because of that”, and Mummy saying, “Well, I expect God will make it up to you when you grow up. You can get married and have some children of your own”, “How do I know I’m not going to marry a drunken man?” That was my greatest fear because I’d seen so many drunken men coming out of the pub in Ireland. I remember saying that to the Reverend Mother, and she said, “There’s plenty of drunken men in England you know!” She was Irish. I grew up in a very, very Catholic family, so God was in everything and, really, God helped all those people, whatever one’s perception of God is. They were helped by their belief and, I think, probably you cling to that as best you can, and you lose it and try and find it again.

What was the culture of drinking at that time?

I think there’s probably an awful lot more now. It’s just when I was a small child I used to be absolutely disgusted by the smell walking past the pub, and I used to be rather frightened if a man came out drunk. I don’t know why I latched onto this possibility that I might suddenly find that I might end up with one of these, but when you’re a child you don’t really know how it works, do you? And why did I never get this feeling here? Well, I think, I never walked past a pub where we lived. Well, there was one at the top of the road, but we never walked close enough to have this smell oozing out of it. It’s changed. Ireland has changed. But 1940s Ireland, and parts of London … I remember hating going to Mass in the church in Hammersmith because of the smell, and it wasn’t a stench smell. It was the pub and the smoke, and really, I think, now looking back, the feeling of poverty. I think it’s the rather stale clothes, the beer. I might be exaggerating a bit there. The Ireland that you know now isn’t the same.

Any other sorts of memories that are relevant to the story of widowhood?

Because we haven’t got conscription now, the people who go into the military are people who, for whatever reason, want to be there, and their families are sort of almost an appendage to that, and probably there is much more of a community spirit. It’s like being in an organisation which maybe transfers from place to place. I’m thinking, really, in terms of the Foreign Office. You’ve got little enclaves of people who belong to the same organisation, who find themselves at a particular place and, therefore, socialise or not, but who are still part of a particular group, and I would think that now, because people aren’t just being called up willy-nilly from here or there or everywhere, people make more of a life within a regiment. Am I talking rubbish?

I think from my mother’s point of view it was quite different because he had just been a bank clerk who decided he really ought to go off and fight. Because it was the wartime and there was a purpose to what they were doing. It wasn’t a job that could be left to one side for the evening and have a bit of socialising. I mean there must have been a bit of socialising, I suppose, but certainly nothing I knew about or that my mother ever talked about. And after he came back [when he didn’t come back], there was no connection at all, apart from coughing up for the fees and the pension. There was no phone call to say “Are you alright Mrs King?” I think she wouldn’t have expected it. She would have dropped dead if it had happened, I’d have thought. There weren’t expectations. They didn’t expect it, but it was just after the event when she used to grumble away when she’d hear the war widows in Germany were living a life of luxury in Germany, and she felt, “Ahem, excuse me!”.

Was your mother a member of the War Widows’ Association?

Yes. I was working at that time for the Jesuits in Farm Street, and they’d had a fundraising thing, and I was in the office doing letters. And there a was particular time of the year when we were very busy. We had to send out and stuff lots of envelopes, and my mother was doing bits of temporary work here and there, and we’d had all sorts of disasters with people coming in and not doing a good job, and I said to my boss, “Look, Mummy is available. She won’t be a disaster. She’ll come in and do the job”. So she came in, and we were both working away, and it was a routine envelope-stuffing job, and we were listening to the radio, and they were interviewing Mrs Jill Gee, who had just started the War Widows’ Association, and Mummy said, “That is a good idea. I’m going to join”. So, she joined, but she didn’t want to go and do anything. She just wanted to pay her dues, and she just kept an eye on what they were doing, and she used to enjoy watching, and when she died I then became an Associate Member, which is why they send me Courage, and that’s where I saw your advertisement.

This interview transcript, its print and online versions, and the corresponding audio files are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives Licence. This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as the work in question is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to War Widows’ Stories. If you wish to use this work in ways not covered under this licence, you must request permission. To do so, and for any other questions about this interview, how you may use it, or about the project, please contact Dr Nadine Muller via email (info@warwidowsstories.org.uk), or by post at the following addressing: John Foster Building, Liverpool John Moores University, 80-98 Mount Pleasant, Liverpool, L3 5UZ.